Abstract

Postharvest losses of sweet orange fruits in Nigeria are considerable and often impacts negatively on economic returns and food security. Edible oil coatings have the potential to extend shelf life and enhance postharvest fruit quality. This study evaluated the effect of edible coatings of Moringa and sesame seed oils on biochemical quality of sweet orange fruits stored under ambient conditions. Harvested fruits of Ibadan sweet and Valencia cultivars were coated with Moringa seed oil (MSO) and Sesame seed oil (SSO) at three concentrations (0%, 1% and 2%) to determine the effect on biochemical attributes of fruits over a 30 day period. The experiment was a 2×2×3 factorial laid out in Completely Randomized Design (CRD) and replicated 3 times. Results indicated significant influence of treatments on biochemical attributes evaluated. Ibadan sweet had higher pH, reducing sugar and Vitamin C while Valencia recorded higher titratable acidity (TA) and total soluble solids (TSS). Fruits coated with SSO had lower TA and TSS but higher pH except on day 30, while those treated with MSO had comparatively higher TA, TSS, Vitamin C and reducing sugar. There was a clear pattern of increase in Vitamin C as oil concentration increased. Generally, TA and TSS increased as storage duration increased while pH, reducing sugar and Vitamin C content deceased with time. Fruit coating improved postharvest quality of orange fruits with MSO doing better than SSO. These can therefore be used to preserve postharvest quality of sweet orange fruits.

Introduction

Citrus spp. (Rutaceae) is believed to be the most widely produced fruits in the world. In 2017, production was put at 146,599,168 tons with oranges accounting for 50% of total citrus production. Other citrus species under production are mandarin and tangerines (22.8%), lemons and limes (11.7%), and grapefruit and shadok. (6.2%) (FAO, 2017). Among factors accounting for its importance are the high concentration of ascorbic acid in the fruit pulp and the high industrial potential (Davies and Albrigo, 1994). Internationally, citrus fruit market consists of the processed fruit, represented mainly by extracted orange juice, and the fresh fruit market (Olife et al., 2015). Although juice extraction, holds precedence over fresh whole fruit for direct consumption. Spain is the leading country for exports of fresh produce (FAO, 2013).

Major citrus producing countries in the world are China, followed by Brazil, USA, India, Mexico and Spain (FAOSTAT, 2017). In Nigeria, there is a sizeable level of production of citrus especially sweet oranges. Nigeria has been ranked 9th in global citrus production. Much of the production resides within the middle belt region (Aiyelaagbe et al., 2001), with Benue state taking the overall lead (Avav and Uza, 2002). Although produce from the country does not feature in the international market (UNCTAD, 2010), there however, seem to exist an informal market in citrus fruits between Nigeria and some of her neighbours particularly Niger and Chad. This is in addition to a more or less robust internal market for fresh fruits. At any rate, as obtain elsewhere, citrus cultivation has both financial and nutritional benefits to the producers (Otieno, 2020).

Postharvest fruit losses are a problem globally, being more serious in developing than the developed countries (Hodges et al., 2011). This is particularly true of perishable commodities such as fruits and vegetables (Aulakh et al., 2013). In Nigeria, there are substantial post harvest losses of fresh fruits including citrus. Measures commonly employed elsewhere in control of postharvest food losses such as chemical preservatives, refrigeration, controlled and modified atmosphere packaging (Zhang and Quantick, 1997) may not be applicable in the Nigerian rural context due to unreliable power supply. Use of chemical preservatives is laden with consumer safety concerns.

In the light of the above, a search for effective options that are cheap, safe and familiar at the rural level has become impetrative. Edible oil coatings have been credited with extending shelf life of fruits (Park, 1999), improving appearance and consumer appreciation of treated fruits (Perez-Gago et al., 2006), and exhibiting microbial action against decay organisms. Moringa and sesame seeds are commonly found in Nigeria. However, the use of their oil extracts in preservation of fresh fruits has not been studied, at least not to any appreciable degree. The objective of this study therefore was to investigate effects of moringa and sesame seeds oils on biochemical changes of two sweet orange varieties stored under ambient conditions.

Material and Methods

Mature fruits of sweet orange varieties - Ibadan sweet and Valencia - were harvested from a private farm in Vandeikya Local Government Area of Benue State. Each variety was harvested from one stand and fruit placed in plastic crates and transported under cool weather to Makurdi for the storage trial in April, 2018.

Sufficiently dried seeds of Moringa (Moringa oleifera) and sesame (Sesamum indicum) were subjected to local cold press extraction method to extract the oil. A 1g carboxyl methyl cellulose (CMC) was dispersed in 100ml distilled water with glycerol at 0.5% (v/v) was added as plasticider. The dispersion was heated at 85 °C for 5 minutes with subsequent cooling at room temperature (Sayanjali et al., 2011). Sesame seed oil (1% and 2% v/v) and moringa seed oil (1% and 2% v/v) were incorporated into CMC coating solutions. Orange fruits were previously immersed in sodium hypochlorite solution (1% v/v) for 5 minutes and then washed with potable water and left for 1hr to air dry. The fruits were then immersed for three minutes in the coating solutions containing different combinations of CMC essential oil concentrations (0, 1 and 2 %) and gently shaken with a glass stem for 1 minute. The fruits were dried on a nylon filter to drain the excess liquid and packed in a netted plastic container. These were stored under ambient conditions in the laboratory.

The experiment was a 2×2×3 factorial made up of variety (Ibadan Sweet and Valencia), edible oil type (Moringa seed oil, MSO, and Sesame seed oil, SSO) and oil concentration (0%, 1% and 2%). Factorial combinations were arranged in completely randomized design (CRD) with 3 replicates. The 0% acted as the control and was made up of distilled water only. Each experimental unit had 36 fruits giving a total of 1296 fruits. Biochemical changes, namely, total soluble solids, ascorbic acid, reducing sugar, pH and titratable acidity were monitored at 5-day intervals up to 30 days of fruit storage.

Biochemical changes were estimated based on standard procedures as outlined by the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC, 2005). The total soluble solids (SS) (°Brix) content was determined with a digital refractometer (Model HI 96801, Hanna Instruments, São Paulo, Brazil), and the result was expressed as °Brix (Meng et al., 2008).

Determination of titratable acidity (TA) was done with phenolphthalein as an indicator with 0.1 N NaOH, and the result was expressed as mmolHþ/100 g of fruit (Meng et al., 2008).

Reducing sugar was determined by titrating 100 ml of diluted juice against Fehling’s solution till the appearance of brick red precipitates. A pH meter (Model No HANNA B 417) was employed for determination of pH value. Ascorbic acid content was measured using 2, 5-6 dicholorophenol indophenols’ method described by A.O.A.C (2005).

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was performed on all data collected using Genstat statistical software. Significant means were separated using the least significant difference (F-LSD) procedure at 5% probability level.

Results and Discussion

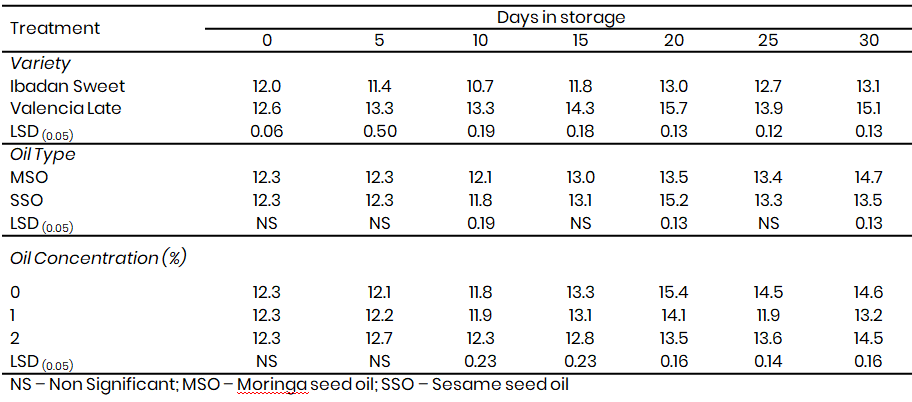

Key weather variables that prevailed during the period of the experiment are summarized in Table 1. Temperature varied from 29.8 to 34.0 oC. Relative humidity ranged from 65.8 to 80.6%. Unlike temperature, RH generally increased from the beginning of the study to the end. Table 2 is a summary of the main effects of variety, oil type and concentration on total soluble solids (TSS) content of stored sweet orange fruits. Valencia Late had a significantly higher TSS (°Brix) compared to Ibadan sweet. Throughout the duration of the experiment, oil type did not have consistent influence on fruit TSS. At 10 days of storage, fruits coated with MSO showed higher TSS values. Ten days later, the reverse was the case, although at the end of the storage period, MSO coated fruits recorded higher TSS values than those coated with SSO. Oil concentration showed significantly higher values at 10 – 30 days of storage. Interestingly, as from 15 days of storage, control fruits had higher TSS than coated ones. However, at the end of storage (30 days), uncoated fruits and those coated with 2 % edible oil gave statistically similar TSS values which were higher than those of the 1 % oil concentration.

Table 1: Temperature and Relative Humidity during the period of storage

Table 2: Effect of variety, oil type and concentration on Total Soluble Solids (TSS) (oBrix) of stored sweet orange fru

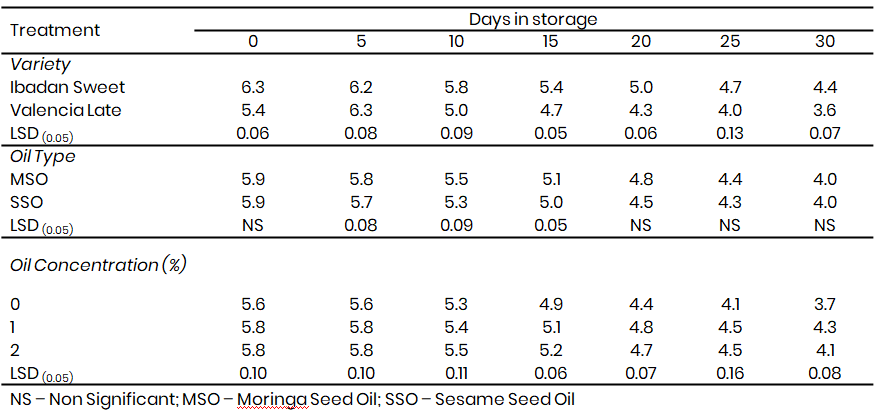

Effect of the factors on reducing sugar content is presented in Table 3. Ibadan sweet showed superior reducing sugar levels throughout the period of the experiment except at 5 days of storage. From 5 – 15 days, MSO had more favourable effect on reducing sugar content than SSO. Though no significant effect on this quality was observed between MSO and SSO, it was evident that coated fruits gave statistically higher reducing sugar values than the uncoated ones throughout the storage period.

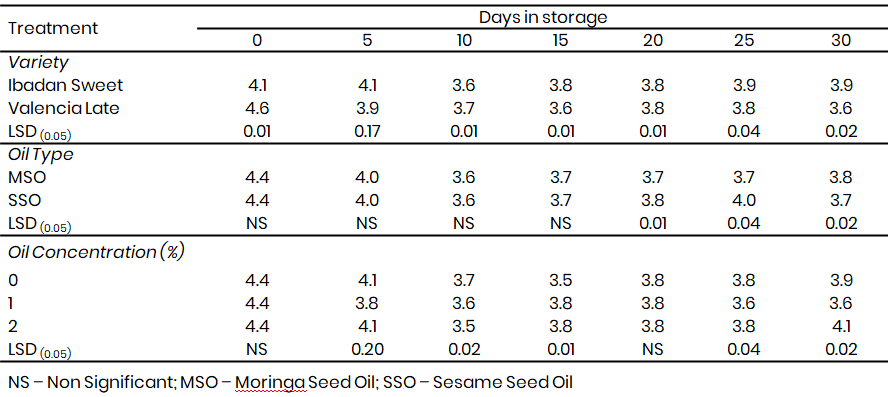

Varietal influence on titratable acidity (TA) was significant throughout the study duration. Generally, Valencia recorded higher levels of titratable acidity than Ibadan sweet (Table 4). Also fruits coated with MSO were generally higher in TA concentration except at 25 and 30 days of storage when those differences cancelled out. Coating of fruits also led to higher production of TA compared to those that were not coated. Influence of sweet orange variety, edible oil type and concentration on pH of stored fruits is presented in Table 5. Generally, fruits of Ibadan sweet variety had higher pH values than those of Valencia. Effect of oil type on pH of stored fruits was not consistent. It was observable that coating of fruits with edible oils at 1% and 2% gave rise to fruits with lower pH values.

Table 3: Effect of variety, oil type and concentration on reducing sugar content (%) of stored sweet orange fruits

Table 4: Effect of variety, oil type and concentration on titratable acidity (%) of stored sweet orange fruits

Table 5: Effect of variety, oil type and concentration on pH of stored sweet orange fruits

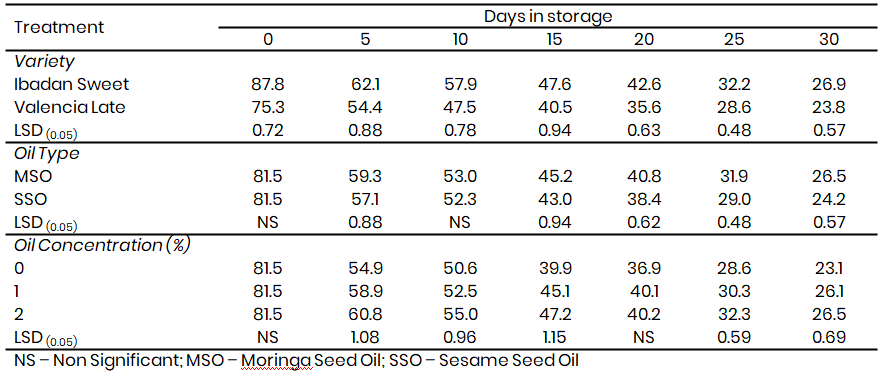

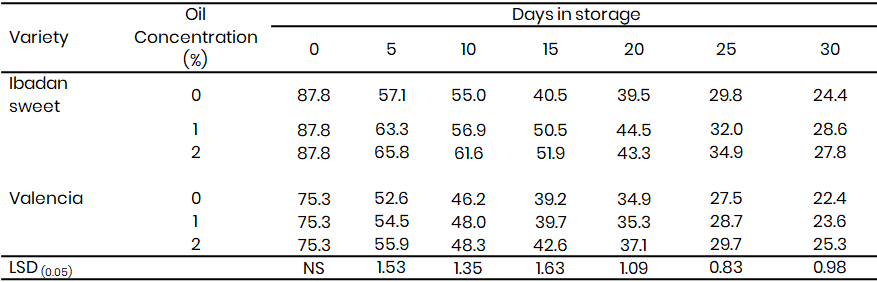

All three factors – variety, edible oil type and concentration – significantly influenced vitamin C content of fruits throughout the period under consideration (Table 6). Ibadan sweet maintained a consistent lead in vitamin C content throughout the period of the experiment. MSO also showed a better ability to retain vitamin C content of fruits as storage progressed. Coating of fruits enhanced their ability to retain vitamin C. Generally, an increase in vitamin C reduction was observed as oil concentration moved from 0% to 2%.

Table 6: Effect of variety, oil type and concentration on Vitamin C content (mg 100g-1) of stored sweet orange fr

Significant interaction was observed between variety and oil concentration on vitamin C content of stored fruits (Table 7). Although vitamin C content of fruits increased with increase in oil content for both varieties, at 30 days of storage, 1 % oil concentration gave` significantly higher vitamin C content (28.6%) compared with the 2 % oil concentration (27.8%). Generally, there was an increase in TSS and TA as storage progressed while reducing sugar, pH and vitamin C content decreased with increase in time of fruit storage.

The higher TSS values of Valencia, as compared with Ibadan sweet conforms to established opinion. Valencia has been noted as the most widely cultivated sweet orange cultivar globally (Saunt, 1990). It has also been acclaimed the most preferred by consumers due to its attractive colour and high TSS and juice content (Davies and Albrigo, 1994). Processors also place high value on it as they utilize it in blending with lower quality juices to improve their taste. It is thus obvious that this variety could be consumed as fresh fruit and as processed juice. Since seeds coated with MSO had higher TSS at the end of the storage period, it is logical that this coating be adopted for better retention of TSS particularly when storage period is to be extended.

TA and pH followed similar pattern. Thus, surprisingly, Valencia had higher TA than Ibadan Sweet. Although the percentage fruit weight loss of the two varieties as earlier reported (Ugese et al., 2018) did not show statistical significance, it is very likely that juice volume of Ibadan Sweet was a bit higher than that of Valencia. As such for equivalent volume of juice tested, TA tended to be higher in Valencia than Ibadan Sweet. Unfortunately, juice volume was not measured in this experiment. Otherwise, results could purely be based on varietal differences that may have little or nothing to do with juice volume.

It is surprising that Ibadan Sweet contained statistically more Vitamin C than Valencia, which is acclaimed the most popular sweet orange variety worldwide (Saunt, 1990). This may give additional impetus to the rising popularity of Ibadan Sweet among Nigerian citrus growers particularly those in Benue State.

The higher TSS values of Valencia, as compared with Ibadan sweet conforms to established opinion. Valencia has been noted as the most widely cultivated sweet orange cultivar globally (Saunt, 1990). It has also been acclaimed the most preferred by consumers due to its attractive colour and high TSS and juice content (Davies and Albrigo, 1994). Processors also place high value on it as they utilize it in blending with lower quality juices to improve their taste. It is thus obvious that this variety could be consumed as fresh fruit and as processed juice. Since seeds coated with MSO had higher TSS at the end of the storage period, it is logical that this coating be adopted for better retention of TSS particularly when storage period is to be extended.

TA and pH followed similar pattern. Thus, surprisingly, Valencia had higher TA than Ibadan Sweet. Although the percentage fruit weight loss of the two varieties as earlier reported (Ugese et al., 2018) did not show statistical significance, it is very likely that juice volume of Ibadan Sweet was a bit higher than that of Valencia. As such for equivalent volume of juice tested, TA tended to be higher in Valencia than Ibadan Sweet. Unfortunately, juice volume was not measured in this experiment. Otherwise, results could purely be based on varietal differences that may have little or nothing to do with juice volume.

It is surprising that Ibadan Sweet contained statistically more Vitamin C than Valencia, which is acclaimed the most popular sweet orange variety worldwide (Saunt, 1990). This may give additional impetus to the rising popularity of Ibadan Sweet among Nigerian citrus growers particularly those in Benue State.

Table 7: Interactive effect of variety and oil concentration on Vitamin C content (mg 100g-1) of stored sweet ora

References

Abad Ullah, N. A. A., Shafique, M., & Qureshi, A. A. (2017). Influence of edible coatings on biochemical fruit quality and storage life of bell pepper cv. “Yolo Wonder.” Journal of Food Quality, 2017, Article ID 2142409. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/2142409

Aiyelaagbe, I. O. O., Afolayan, S. O., Odeleye, O. O., Ogungbayigbe, L. O., & Olufolaji, A. O. (2001). Citrus production in the savannah of western Nigeria: Current status and opportunities for research input. In Book of Abstracts and Proceedings (on CD-ROM), Deutscher Tropentag 2001 Conference on International Agricultural Research for Development (p. 33). University of Bonn, Germany.

Alhassan, U., Amaglo, N. K., & Sefa-Dedeh, S. (2014). Total soluble solids (TSS), titrable acidity (TA) and TSS/TA ratio of harvested sweet orange stored for 26 days. International Journal of Development Research, 4(6), 1404–1407.

Ali, M., Maqbool, S. R., & Alderson, P. G. (2010). Gum arabic as a novel edible coating for enhancing shelf-life and improving postharvest quality of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) fruit. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 58(1), 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2010. 05.001

Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC). (2005). Official methods of analysis (18th ed.). AOAC International.

Aulakh, J., Regmi, A., Fulton, J. R., & Alexander, C. (2013). Estimating post-harvest food losses: Developing a consistent global estimation framework. Proceedings of the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association’s 2013 AAEA & CAES Joint Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA.

Avav, T., & Uza, D. V. (2002). Agriculture. In A. L. Pigeonniere (Ed.), Africa Atlases: Nigeria (pp. 92–95). Les Editions J. A.

Ayranci, E., & Tunc, S. (2004). The effect of edible coatings on water and vitamin C loss of apricots (Armeniaca vulgaris Lam.) and green peppers (Capsicum annuum L.). Food Chemistry, 87(3), 339–342.

Chowdhury, M. G. F. (2018). Postharvest heat stress and semi-permeable fruit coating to improve quality and extend shelf life of citrus fruit during ambient temperature storage [Doctoral dissertation, University of Florida]. University of Florida Digital Collections.

Davies, F. S., & Albrigo, L. G. (1994). Citrus. CAB International.

Copyright

Open Access: This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.