Ergonomic risks of crop production activities among agricultural workers in Ekiti State, Nigeria

Abstract

The study shed lights on the significant ergonomic risks faced by agricultural workers during crop production activities in Ekiti State, Nigeria. It utilized data collected from 120 farm workers through questionnaires and interviews using a multi-stage sampling procedure. Descriptive statistics and a multivariate probit model were employed for data analysis. The study found that the majority (60.8%) of agricultural workers in Ekiti State, Nigeria, were male, with an average age of around 43 years. They reported various ergonomic hazards, including body pain (73.3%), cut from farm implements (73.3%), sprain (64.2%), eye problems (56.7%) and respiratory tract irritation (55%). Musculoskeletal injuries such as lower back pain (77.5%), upper back pain (74.2%), shoulder pain (67.5%), wrist/hand pain (65.8%) were prevalent among the workers. Factors such as sex, age, education, experience, farm size, credit access, safety training, work hours, spraying hours, and chemical exposure were significant in predisposing workers to ergonomic risks. Constraints to safe farm practices included inadequate finance for machinery (86.7%), poorly designed implements (83.3%), lack of safety training from extension agents (74.2%), inadequate knowledge of farm safety measures (59.2%) and constant mechanical hazards due to faulty or bad machineries or equipment (56.7%). Regular training on musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) and safety, along with using improved agricultural equipment, safe work methods, and proper postures, can help mitigate ergonomic risks and improve the quality of life for agricultural workers in the study area.

Introduction

The agriculture sector plays a crucial role globally in meeting human needs by providing food, employment, and raw materials for industries. In Nigeria, agriculture is a vital sector, with approximately 75 percent of the population relying on it as their main source of livelihood (Anderson et al., 2017). Crop production, in particular, drives the agricultural sector, accounting for a substantial portion of Nigeria’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Olowogbon et al., 2021). In the second quarter of 2023, the agricultural sector contributed around 21 percent to Nigeria’s GDP, with crop production alone covering nearly 19 percent (Statista, 2023). Crop production involves the intentional and continuous process of cultivating diverse plants with the primary goal of producing food for human consumption and feed for the livestock industry. Additionally, it serves other purposes such as providing medicinal resources, generating foreign exchange through exports, and supplying materials for commercial and industrial purposes (Mamai et al., 2020).

The agriculture sector poses inherent risks to workers (Babu, 2016), with manual labour being a predominant feature due to the lack of mechanized farming in Nigeria. Human power accounts for approximately 90% of the energy sources in agricultural activities, leading to prolonged periods of working in awkward body positions (Abubakar et al., 2023). This can result in static contraction of muscles, reduced blood flow, and ultimately, increased body pain and decreased productivity (Mulyati et al., 2019). These extreme working conditions contribute to the development of Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSDs), which are recognized as the most prevalent safety issue in agriculture (Eguoaje et al., 2019). The lack of proper equipment and poor knowledge of ergonomics exacerbate these problems, highlighting the need for ergonomics to play a significant role in addressing and reducing musculoskeletal injuries among agricultural workers (Prasad et al., 2019).

Ergonomics, as a multidisciplinary science, focuses on creating a better match between the job and the worker to ensure their health and safety. It involves designing and arranging work environments and tools in a way that promotes ease of use and safety for workers (Naeini et al., 2014; Vyas and Bajpal, 2016). The International Ergonomics Association defines ergonomics as the science of understanding the interaction between humans and various elements of a socio-technical system. In crop production, the use of herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, and other agrochemicals is essential for protecting crops from weeds, insects, and diseases (Richardson et al., 2019). However, exposure to these chemicals poses significant ergonomic and occupational risks, leading to both acute and chronic health issues for agricultural workers (Vyas, 2020). Despite the importance of ergonomics in promoting a safe and healthy relationship between work, workers, and their environment (Vyas and Bajpal, 2016), deliberate efforts to reduce ergonomic-related injuries in Nigerian agricultural workplaces have been lacking (Olowogbon et al., 2021). Therefore, this study aims to investigate the ergonomic risks associated with crop production activities among agricultural workers in Ekiti State, Nigeria. Specifically, the study assessed the prevalent ergonomic risk hazards among the agricultural workers, determined factors predisposing agricultural workers to ergonomic risk hazards, and identified the constraints to safe farm practices.

Material and Methods

The study was conducted in Ekiti State, Nigeria, which was formed from Ondo State on October 1, 1996, with its capital in Ado-Ekiti. Located at coordinates 7°40'N 5°15'E, Ekiti State is bordered by Kwara State to the north, Kogi State to the northeast, Ondo State to the south and southeast, and Osun State to the west. The state comprises 16 Local Government Areas (LGAs) and has a population of approximately 2,384,212 people, spread across an area of approximately 5,887.890 square kilometres. Agriculture serves as the backbone of the state’s economy, with crops such as yam, rice, cassava, cocoa, among others, cultivated both for subsistence and commercial purposes.

The study utilized a multi-stage sampling technique to choose both the communities and respondents. Firstly, two Local Government Areas (LGAs), Gbonyin and Oye, were purposively selected out of the 16 LGAs in Ekiti State due to their prevalence of farming activities. Secondly, four communities were randomly selected from each of the two LGAs, totalling eight communities. Finally, within each selected community, 15 farmers were randomly chosen using simple random sampling techniques, resulting in a total of 120 respondents for the study. Data were collected through well-structured questionnaires and interview schedules.

Method of data analysis

The data generated on ergonomic hazards and constraints to safe farm practices in the study area were analyzed using descriptive statistics tools such as frequency, percentages, means, and standard deviation. Additionally, a multivariate probit model was employed to determine the factors predisposing agricultural workers to ergonomic risk hazards. This statistical model allowed for the examination of the relationship between multiple factors simultaneously and their influence on the likelihood of experiencing ergonomic hazards.

Multivariate probit (MVP)

In a single-equation statistical model, information on one ergonomic risk hazard experienced by agricultural workers does not affect the likelihood of experiencing another ergonomic risk hazard. However, the MVP approach allows for the simultaneous modelling of the influence of explanatory variables on each different ergonomic risk hazard while considering potential correlations between unobserved disturbances and the relationship between the different hazards (Belderbos et al., 2004). Complementarities (positive correlation) and substitutability (negative correlation) between different symptoms can contribute to this correlation. Failure to account for unobserved factors and interrelationships among ergonomic risk hazards may lead to biased and inefficient estimates (Greene, 2008). The observed outcome of ergonomic risk hazards can be modelled using a random utility formulation. For each agricultural worker (i=1,…., N) facing ergonomic risk hazard j (j = 1,…, j) of crop production activities. Let U0 represent the effects on the worker from traditional management practices, and letUk represent the effects of experiencing kth hazard: (k = PH, MH, CH, EH) denoting physiological hazards (PH). Mechanical hazard (MH), Chemical hazards (CH) and Environmental Hazards (EH) respectively.

The general multivariate probit model is specified as follows:

Yijk*=Xij' βk+Uij k = PH, MH, CH, EH) ------------- (1)

Using the indicator function, the unobserved preferences in equation (1) translate into the observed binary outcome equation for each symptom as follow:

Yk = {(1 if Yijk* >0@0 otherwise)} k = PH, MH, CH, EH) ----(2)

In the multivariate model, where the experience of different hazards is possible, the error terms jointly follow a multivariate normal distribution (MVN) with zero conditional mean and variance normalized to unity (for identification of the parameters) where;

(? =PH, MH, CH, EH) ~??? (0, Ω) and the symmetric covariance matrix Ω is given by

Ω = [(1 PPHMH PPHCH PPHEH PMHPH 1 PMHCH PMHEH PCHPH PCHMH 1 PCHEH PEHPH PEHMH PEHCH 1 )] ------------------ (3)

The off-diagonal elements in the covariance matrix represent the unobserved correlation between the stochastic components of different types of hazards. In equation (3), this assumption means that the Multivariate Probit (MVP) model jointly represents the ability to experience a particular hazard. This specification, with non-zero off-diagonal elements, allows for correlation across the error terms of several latent equations, representing unobserved characteristics that affect the experience of alternative hazards. Essentially, it accounts for the fact that experiencing one type of hazard may be related to experiencing another type of hazard due to common underlying factors or mechanisms.

The model for this study is specified as:

Yὶϳ = β0 + βXji + ε --------------------------------- (4)

Where:

Yὶϳ is a binary dependent variable that takes the value of 1 if the ith agricultural worker reports jth ergonomic risk hazard and 0 otherwise. Following Vyas (2020), the jth ergonomic risk hazards are as stated: Y1 = Physiological hazards; Y2 = Mechanical hazard; Y3 = Chemical hazards; Y4 = Environmental Hazards. Xjὶ is a vector of explanatory variables and is expressed as:X1 = Age of farmer (years); X2= Sex of farmer (dummy); X3 = Educational level (years); X4= household size (Number of people); X5= Farm Size (hectare); X6= Farm work experience (years); X7= Chemical application experience (years); X8= Previous safety training exposure (1 = yes, 0 = otherwise); X9 = Daily working hours (1 – greater than or equal to 6 hours, 0 otherwise); X10= Spraying hours (1 – greater than or equal to 6 hours, 0 otherwise); X11= Credit access (Dummy); X12= Extension contacts (Dummy).

Results and Discussion

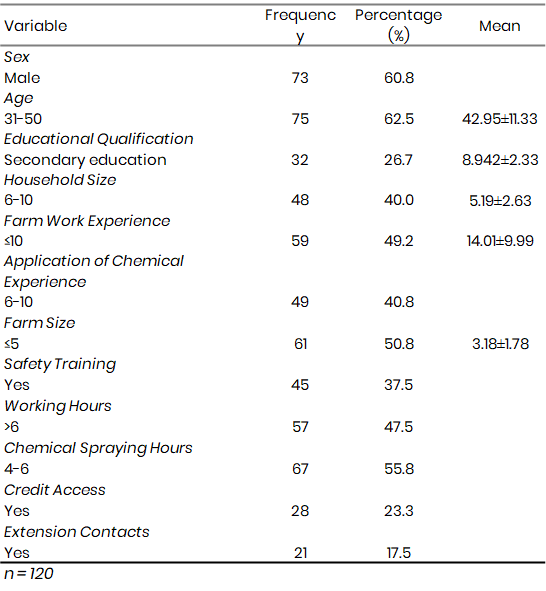

Results of the socio-economic variables included in the model are presented in Table 1. The result reveal that majority (60.8%) of the sampled agricultural workers were male, 62.5% were aged between 41 and 50 years with an average age of about 43 years which indicates that the workers were relatively young and within their economically active years. The average years of schooling of about 9 years suggests that most respondents had secondary education. About 40% of the respondents had between 6 and 10 persons in their family. The mean family size was about 5 persons, indicating that the workers generally had small family sizes. Almost half (49.2%) of the workers had less than 10 years of experience as agricultural workers, while 40.8% had between 6 to 10 years of experience in chemical application. The mean years of experience were 14, indicating that workers had substantial experience in the agricultural sector, which could influence the adoption of safe farm practices. The average farm size was 3 hectares, suggesting that respondents were predominantly working on small-scale farms.

Only 37.5% of the workers had undergone safety training, potentially impacting safe farm practices. Approximately 47.5% of the respondents worked for less than 6 hours daily, while 55.8% applied chemicals for duration of 4 to 6 hours daily. Access to credit facilities and extension services was limited, with only a few (23.3% and 17.5%, respectively) having access. This could negatively impact the adoption of innovations and safe farm practices.

Table 1: Summary of selected socio-economic characteristics of the respondents

Agricultural workers self-reported ergonomic hazards in the study area

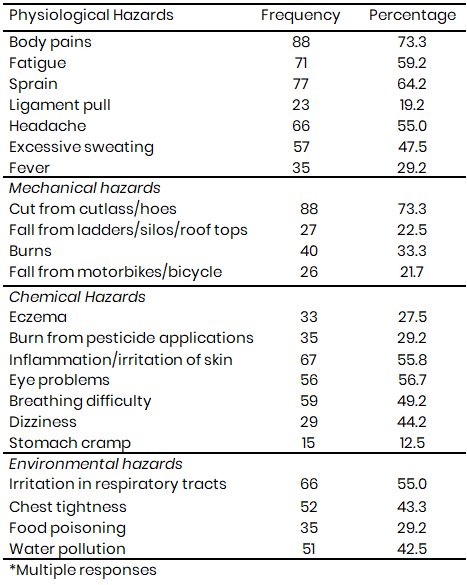

Work related ergonomic injuries have been identified to be prevalent among the workers. Following Vyas (2020), these injuries were classified in Table 2 and discussed below:

Physiological hazards

Physiological hazards typically arise from prolonged hours of vigorous work, repetitive movement, carrying heavy loads, exhaustion, and assuming awkward postures while working. The results in Table 2 indicate that the major physiological hazards experienced by workers in the study area include body pain (73.3%), sprains 64.2%), fatigue (59.2%), and headaches (55%). This finding is consistent with previous research by Ajay et al., (2021) which highlighted that farm labourers often experience musculoskeletal injuries due to activities such as repetitive bending, twisting, lifting heavy items, and continuous motions when working for long hours.

Mechanical hazards

Mechanical hazards in agriculture often stem from farm equipment and tools, leading to injuries such as cuts, falls, and burns. In the study area, the various mechanical hazards reported by agricultural workers include: Cuts from cutlass and hoes, resulting in injuries to 73.3% of the workers, burns from chemical application, causing injury to 33.3% of the workers, falls from ladders, silos, and rooftops, which were a source of injury for 22.5% of the workers and falls from motorcycles or bicycles during farming operations, affecting 21.7% of the workers. Ergonomic measures such as providing protective gear, ensuring equipment is in good working condition, and implementing safety guidelines can help reduce the incidence of mechanical hazards and promote a safer working environment for agricultural workers.

Chemical hazards

Chemical hazards in agriculture, such as contact dermatitis or eczema, are often caused by exposure to pesticides and other chemical products used for plant protection (Vyas, 2020). The results in Table 2 indicate the following reported chemical hazards among workers in the study area: Eye problems, including redness of eyes, watering, burning sensation and, irritation were reported by 56.7% of the workers; Skin problems, such as burning, inflammation, and irritation of the skin, were reported by 55.8% of the workers while handling chemicals. Breathing difficulties when spraying chemicals were reported by 49.2% of the workers and 44.2% of the workers reported experiencing giddiness when inhaling chemicals accidentally or when exposed to pungent smells. Ajay et al., (2021) reported similar results for workers in India.

Environmental hazards

Environmental hazards in agriculture pose risks such as air and water pollution, respiratory irritants, and food poisoning. The self-reported ergonomic environmental hazards experienced by workers presented in Table 2, reveals that around 55% of the workers had respiratory problems such as irritation in respiratory tract, while 43.3% had chest tightness. Water pollution was a major hazard to 42.5% and food poisoning was experienced by 29.2% of the workers in the study area. These findings underscore the significant health risks posed by environmental hazards in agriculture, including respiratory issues, water pollution, and food borne illnesses. The findings are consistent with previous research by Vijay (2014); Andersson and Treich (2014) highlighting the elevated risk of respiratory conditions such as hypersensitivity pneumonitis, asthma, bronchitis, tuberculosis, pneumonia, influenza and death among farm workers. Implementing measures to mitigate environmental hazards, such as proper ventilation, water management practices, and food safety protocols, can help reduce the incidence of these ergonomic hazards and promote the health and safety of agricultural workers.

Table 2: Self-reported ergonomic hazards experienced by the workers

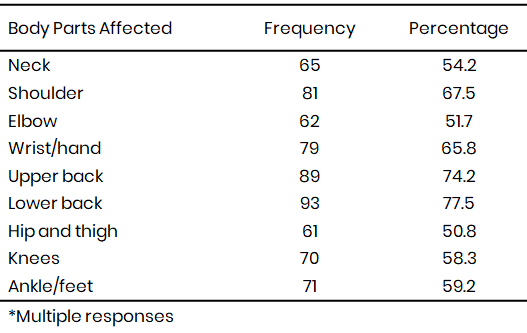

Musculoskeletal problems and body discomfort during crop production activities

Musculoskeletal problems and discomfort among agricultural workers are often attributed to the physical demands of agricultural production activities, including lifting handling of heavy loads; static positioning, squatting and continuous bending. These activities can lead to work-related musculoskeletal injuries, resulting in pain in various parts of the body such as the shoulders, neck, back, nerves and wrists. Additionally, the use of traditional tools and methods in agriculture may further increase the risk of musculoskeletal injury due to the high level of human energy required (Vyas, 2014). The results presented in Table 3 indicate that lower back pain, experienced by 77.5% of the respondents was the most prominent musculoskeletal injury reported by respondents in the study area. Other reported musculoskeletal injuries included upper back pain (74.2%), shoulder pain (67.5%), wrist/hand pain (65.8%), ankle/feet pain (59.2%), knee pain (58.3%), neck pain (54.2%), elbow pain (51.7%), and hip and thigh pain (50.8%). This suggests that respondents had experienced multiple musculoskeletal injuries during their farming operations.

These findings are consistent with previous research, such as the study by Abubakar et al., (2023), which reported work-related musculoskeletal discomfort among farmers in North-Western Nigeria, particularly in the neck, wrist/hand, upper back, and lower back. Moreover, Vyas (2014) highlighted that disorders in the lower back are frequently associated with activities involving lifting and carrying heavy loads. The repetitive or prolonged exertion of static force during such activities can lead to strain and injury in the lower back region. Similarly, upper limb disorders, affecting areas such as the hands, wrists, fingers, arms, neck, elbows, and shoulders, may result from prolonged laborious or perceptible effort. Tasks requiring repetitive movements or sustained static postures can lead to strain and discomfort in these upper limb areas. Additionally, such activities can exacerbate existing musculoskeletal issues or contribute to the development of new ones.

Table 3: Musculoskeletal problems and body discomfort experienced by workers

Frequency (%) of musculoskeletal hazards experienced by farmers/week

The results presented in Table 4 indicate the frequency of ergonomic-related pains reported by the respondents on a weekly basis. The result reveals that 20% of the respondents reported neck pain twice in a week, 23.3% reported should pain thrice a week, elbow pain was reported once by 22.5% of the respondents, wrist/hand pain was reported thrice by 26.7% while 44%, 55.8% and 30% reported to always experience upper back, lower back and hip/thigh pains respectively. Furthermore, knee and ankle/feet pains were reported thrice a week by 24.2% and 30% respectively. These findings highlight the significant prevalence of ergonomic-related pains among agricultural workers on a weekly basis, which could have negative consequences on the health and productivity of the workers. Similar results were reported by Olowogbon et al., (2021), indicating a consistent pattern of ergonomic-related issues among agricultural workers.

Table 4: Frequency (%) of musculoskeletal hazards experienced by workers/week

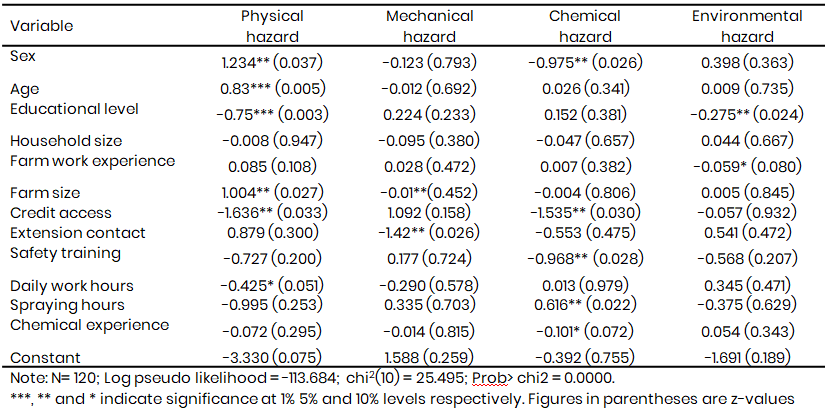

Factors predisposing agricultural workers to ergonomic risk hazards

The results of the multivariate probit model, which examined factors predisposing agricultural workers to ergonomic hazards in the study area, are presented in Table 5. The model was estimated jointly for four ergonomic hazards: physiological, mechanical, chemical, and environmental. The Wald test statistic for the overall significance of the model yielded a p-value of 0.000, indicating that the multivariate probit regression is highly significant overall. This suggests that the combined effect of the explanatory variables on the four ergonomic hazards is statistically significant. The results are presented below:

Physiological hazards

The coefficient of sex was positive and significant (p<0.05), indicating that being male increases the probability of experiencing physiological hazards. Male agricultural workers may be more susceptible to musculoskeletal disorders due to occupational exposures. Additionally, the coefficient of age was positive and significant (p<0.01), indicating that older workers are more likely to experience physiological hazards. This finding is consistent with those of Tonelli et al., (2014) indicating that aging farmers are at higher risk of musculoskeletal disorders, possibly due to prolonged exposure to physical strain over their careers.

In the same vein, the coefficient of farm size was positive and significant (p<0.05), suggesting that workers on larger farms are more likely to experience physiological hazards. This may be attributed to the increased physical demands associated with managing larger agricultural operations.

Conversely, the coefficient of education was negative and significant (p<0.01), indicating that workers with higher levels of education are less likely to experience physiological hazards. This suggests that education may provide individuals with knowledge and skills to adopt safer work practices and reduce the risk of musculoskeletal disorders. The coefficient of credit access was negative and significant (p<0.05), suggesting that workers with access to credit are less likely to experience physiological hazards. Access to credit may enable farmers to invest in mechanization or other technologies that reduce physical strain and improve working conditions. Also, the coefficient of daily hours worked was negative and significant (p<0.10), indicating that working fewer hours per day reduces the likelihood of experiencing physiological hazards. This underscores the importance of managing workload and avoiding excessive physical exertion to prevent musculoskeletal injuries.

Mechanical hazards

The coefficient of farm size was negative and significant (p<0.05), indicating that larger farm size is associated with a lower probability of experiencing mechanical hazards. This suggests that workers on smaller farms may face higher risks of mechanical hazards, possibly due to limited access to mechanized equipment or higher reliance on manual labour. Additionally, the coefficient of the frequency of extension visits was negative and significant (p<0.05), indicating that regular visits from extension agents are associated with a lower probability of experiencing mechanical hazards. Extension agents play a crucial role in providing training, guidance, and support to farmers, including information on safety practices and equipment maintenance, which can help reduce the risk of mechanical injuries.

Chemical hazards

The coefficient of spraying hours was positive and significant at the 5% alpha level, indicating that longer hours of chemical application are associated with a higher probability of experiencing chemical hazards. This finding aligns with findings of Olowogbon et al., (2021), suggesting that prolonged exposure to chemical spraying activities increases the risk of chemical-related health problems. On the other hand, the coefficient of credit access was negative and significant (p<0.05), suggesting that workers with access to credit are less likely to experience chemical hazards. Access to credit may enable farmers to invest in safer equipment, protective gear, and training, thereby reducing the risk of chemical-related health issues. Furthermore, the coefficient of safety training was negative and significant (p<0.05), indicating that workers who had undergone training in the safe use and application of farm chemicals are less likely to experience chemical hazards. In addition, the coefficient of chemical application experience was negative and significant at the 10% level, suggesting that workers with previous experience in chemical application are less likely to experience chemical hazards. This highlights the importance of hands-on experience and familiarity with chemical handling procedures in reducing the risk of chemical-related health problems.

Environmental hazards

The probability of experiencing environmental hazards was significantly influenced by education, with a p-value less than 0.05. A year increase in years of schooling led to a 0.0275% decrease in the probability of experiencing environmental hazards. This suggests that higher levels of education are associated with a reduced likelihood of encountering environmental hazards in agricultural work settings. Education may equip individuals with knowledge and awareness of environmental risks and safety practices, enabling them to mitigate hazards effectively. The probability of experiencing environmental hazards was also influenced by working experience, with a p-value less than 0.10. A year increase in working experience led to a 0.056% decrease in the probability of experiencing environmental hazards. This indicates that individuals with more experience in agricultural work are less likely to encounter environmental hazards, possibly due to their familiarity with safety protocols and effective risk management strategies. This finding supports the submission of Olowogbon et al., (2021) that years of agricultural engagement is expected to influence the acquisition of skills and capability to adopt technological innovation in crop production activities.

Table 5: Factors predisposing crop farmers to ergonomic risk hazards

Constraints to safe farm practices in the study area

The results presented in Table 6 highlight the major constraints to safe farm practices identified by agricultural workers in the study area. These constraints include:

- Inadequate finance for machinery purchase: The majority (86.7%) of respondents reported inadequate finance as a significant constraint to safe farm practices. This suggests that limited financial resources hinder farmers’ ability to invest in modern machinery and equipment, which are essential for improving efficiency and reducing ergonomic risks in agricultural operations.

- Poorly designed implements: A large proportion (83.3%) of respondents identified poorly designed implements as a major constraint. This indicates that the design and functionality of agricultural tools and equipment may not adequately address ergonomic considerations, leading to increased risk of injuries and discomfort among workers.

- Inadequate extension agents to train workers on farm safety: A substantial percentage (74.2%) of respondents reported a lack of extension agents as a significant constraint. Extension agents play a pivotal role in providing farmers with information, training, and support on safety practices and technologies. The shortage of extension agents may limit farmers’ access to essential safety resources and knowledge.

- Inadequate knowledge/awareness of farm safety measures: A considerable proportion (59.2%) of respondents indicated inadequate knowledge and awareness of farm safety measures as a constraint. This suggests that there is a need for improved education and training initiatives to enhance farmers’ understanding of safety practices and promote a culture of safety in the agricultural sector.

- Constant mechanical hazards due to faulty or bad machineries or equipment: More than half (56.7%) of the respondents reported constant mechanical hazards as a significant constraint. This highlights the prevalence of equipment malfunction or deterioration, which poses risks to worker safety and productivity.

These findings align with previous research by Olowogbon et al., (2021), which also identified similar constraints to safe farm practices in North-central zone of Nigeria. By addressing these challenges, it will be possible to create safer and more sustainable working environments for agricultural workers, ultimately improving their well-being and productivity in the study area.

Table 6: Constraints to safe farm practices in the study area

Conclusion

The study concluded that Working in the agricultural sector poses significant ergonomic risks, particularly in terms of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs), which can impact the health and well-being of farm workers. The study identified multiple musculoskeletal injuries among agricultural workers, with lower and upper back pain, shoulder pain, wrist/hand pain, ankle/feet pain, and neck pain being prominent. Factors such as sex, age, education, experience, farm size, credit access, extension contacts, safety training, daily work hours, spraying hours, and chemical experience were found to predispose agricultural workers to various ergonomic risks, including physiological, mechanical, chemical, and environmental hazards. These findings emphasize the need for targeted interventions and strategies to mitigate ergonomic risks and improve the health and well-being of agricultural workers in the study area.

The following recommendations were proposed based on the study’s findings:

- Regular training: Agricultural workers should receive regular training to increase awareness of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) and safety measures. Training programs should focus on the proper use of improved agricultural equipment, personal protective equipment (PPE), safe work methods, and ergonomic postures to reduce the risk of injuries.

- Enhancement of extension services: There is a need to reorient and train extension agents to better educate farm workers on safety practices, particularly regarding pesticide application. Extension services should emphasize the importance of reading and adhering to pesticide labels and manuals to minimize exposure to harmful chemicals.

- Promotion of sustainable farming practices: Farmers should be encouraged to reduce or eliminate the use of synthetic pesticides by transitioning to bio-pesticides and organic farming methods. Governments can support this transition through incentives and legislation that prioritize environmental and worker safety.

- Hazard identification and prevention: There is a crucial need to identify and prevent ergonomic hazards in agricultural work environments. This can be achieved through interventions such as equipment design improvements, enhanced work processes, and increased awareness of risk factors among workers.

References

Abubakar, M. I., Abubakar, M. S., & Alhaji, Y. (2023). Prevalence of musculoskeletal discomforts among rural farmers in North-Western Nigeria. FUDMA Journal of Sciences (FJS), 7(2), 308–312.

Ajay, P. N., Ramanjit, K., Amandeep, S., & Paramvir, S. (2021). Agrarian population’s occupational health risks and after effects. Examines in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 3(2), EPMR.000559. https: //doi.org/10.31031/EPMR.2021.03.000559

Andersson, H. T., & Treich, N. (2014). Pesticides and health: A review of evidence on health effects, valuation of risks, and benefit–cost analysis. Advances in Health Economics and Health Services Research, 24, 203–295.

Anderson, J., Marita, C., Musiime, D., & Thiam, M. (2017). National survey and segmentation of smallholder households in Nigeria: Understanding their demand for financial, agricultural and digital solutions (CGAP Working Paper). Washington, DC: CGAP.

Babu, T. R. (2016). Productivity improvement of agro-based farm workers using ergonomic approach. Productivity, 57(2), 123.

Belderbos, R., Carree, M., Diederen, B., Lokshin, B., & Veugelers, R. (2004). Heterogeneity in R&D cooperation strategies. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 22(8–9), 1237–1263.

Eguoaje, S. O., Evboifo, N. O., Aideloje, V. E., & Okwudibe, H. A. (2019). The role of ergonomics in sustainable agricultural development in Nigeria. Merit Research Journal of Agricultural Science and Soil Sciences, 7(12), 165–169.

Greene, W. H. (2008). Econometric analysis (6th ed., International ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Mamai, O., Parsova, V., Lipatova, N., Gazizyanova, J., & Mamai, I. (2020). The system of effective management of crop production in modern conditions. BIO Web of Conferences, 17, 00027.

Mulyati, G., Maksum, M., Purwantana, B., & Ainuri, M. (2019). Ergonomic risk identification for rice harvesting workers. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on Agricultural and Biosystem Engineering (pp. 1–8). IOP Publishing Ltd.

Copyright

Open Access: This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.