Abstract

This study assesses the effects of more than 35 years of continuous mango cultivation on soil properties at the Institute for Agricultural Research Farm, Samaru, Nigeria, by comparing current soil conditions to legacy data from 1984 using T Student’s independent T-test. Results revealed notable changes in soil properties over time. The results revealed that mango cultivation has led to an increase in soil organic carbon (T=2.21, P=0.075, MD= 4.11 g kg-1), total nitrogen (T=3.78, P=0.009 MD= 2.05 g kg-1) attributed to the decomposition of mango leaves, twigs, and flowers, which contribute to humus formation and improve soil fertility. However, the study also identified a decline in essential nutrients such as calcium, magnesium, and potassium, indicating nutrient depletion likely due to tree uptake and leaching. Soil pH decreased significantly, suggesting acidification, while available phosphorus showed slight improvement over time. Despite these challenges, the overall soil degradation index showed a slight improvement, indicating that mango cultivation, when managed sustainably, can enhance soil quality. To sustain mango cultivation and enhance soil health, integrated nutrient management strategies combining organic and inorganic inputs are recommended. Practices like mulching with mango leaves to boost phosphorus recycling, erosion control measures (cover cropping and contour planting), and the adoption of agroforestry systems to enhance nutrient cycling and diversify income are also proposed.

Introduction

Mango (Mangifera indica) is one of the most popular, nutritionally rich, and economically important fruits globally. Nigeria ranks among the top ten mango-producing countries (Jekayinfa et al., 2013), with major production occurring in states such as Benue, Jigawa, Plateau, Yobe, Kebbi, Niger, Kaduna, Kano, Bauchi, Sokoto, Adamawa, and Taraba (Yusuf and Salau, 2007). The cultivation of mango can help mitigate environmental degradation by reducing soil erosion and improving soil fertility. Mango trees provide shade, which minimizes wind erosion, and their fallen leaves and fruits contribute organic matter to the soil. However, mango productivity is often hindered by decreasing soil nutrient levels and the imbalanced use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides (Balakrishna et al., 2021).

The nutrition of mango trees depends on the soil's inherent ability to supply essential nutrients, which are absorbed by the trees. The availability of these nutrients is vital for effective orchard management (Balakrishna et al., 2021). Nutrient content and availability play a significant role in a plant’s ability to produce fruits and complete its life cycle. Over time, long-term mango cultivation may cause variations in soil nutrients due to clearing native vegetation, applying inorganic chemicals such as fertilizers and pesticides, and routine farm operations (da Silva et al., 2014). These changes can either improve soil properties or accelerate degradation, depending on soil type, management practices, and the duration of cultivation. According to Aminu and Ladan (2021), soil nutrient levels often decline over time following crop harvesting, as nutrients are not replenished. As a result, large quantities of fertilizers are applied, but only a small proportion is absorbed by plants, with the remainder leaching away. This necessitates continuous fertilizer application (Aminu and Ladan, 2021). The extensive use of chemical fertilizers, however, deteriorates soil properties, leading to long-term fertility loss (Aminu and Ladan, 2021).

Despite the significance of mango cultivation, limited research has been conducted on its influence on soil properties in this region. Understanding the changes in soil properties caused by management practices could inform sustainable approaches to mango production while minimizing environmental degradation. Additionally, knowledge of soil nutrient status aids in diagnosing nutritional issues and estimating fertilizer requirements for fruit trees.

Material and Methods

Study area

The Institute for Agricultural Research (IAR) is located in Samaru, Sabon Gari Local Government Area, Northwest Nigeria, between latitudes 11°10′30″N and 11°11′40″N and longitudes 7°36′30″E and 7°38′6″E, covering approximately 227.8 hectares. The precise date of the mango orchard's establishment is not documented; however, available records indicate its existence as far back as 1984. The region has a tropical climate, with annual precipitation ranging from 300 mm to 1000 mm. Rainfall intensity peaks in July and August (Aliyu, 2023). Temperatures vary between 22.18°C and 30.38°C, with the highest values occurring in April, as in other parts of Northern Nigeria. The lowest temperatures, ranging from 22.9°C to 23.1°C, are experienced in December or January (Aliyu, 2023). The mean atmospheric relative humidity ranges between 70–90% during the rainy season and 25–30% during the dry season. High relative humidity is caused by southwest trade winds carrying moisture-laden air from the Atlantic Ocean. In contrast, the low relative humidity between October and March results from the dry, dusty, and cold northeast trade winds originating from the Sahara Desert (Balarabe et al., 2015).

Methodology

Soil samples were collected from a depth of 0–30 cm within the projection area of the canopy in a mango orchard located at the IAR Samaru Farm, Zaria, Nigeria. The samples were air-dried, crushed, and sieved through a 2 mm sieve. Particle size distribution was determined using the Bouyoucos hydrometer method as described by Gee and Or (2002). Soil texture was classified using the USDA textural diagram (Soil Survey Staff, 2017). Bulk density was determined using the core sampling method (Blake and Hartge, 1986).

Soil pH was measured in a 1:2 soil-to-water suspension using a pH meter with a glass electrode, following the method outlined by Jackson (1973). Organic carbon content was estimated using the Walkley and Black (1934) wet oxidation method (Jackson, 1973). Organic matter content was calculated by multiplying the organic carbon content by a factor of 1.724. Exchangeable Bases and Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC) were determined using the 1N neutral ammonium acetate extraction method, following the percolation tube procedure (Van Reeuwijk, 1993). Sodium (Na) and potassium (K) concentrations were measured using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (AAS), while calcium (Ca) and magnesium (Mg) were measured using a flame photometer. Results were expressed in cmol(+) kg⁻¹ of soil. Total Nitrogen was determined by extracting the soil with 1N KCl and using the micro-Kjeldahl distillation method (Agbenin, 1995). Results were expressed in g kg⁻¹ of soil. Available Phosphorus was extracted using 0.5M NaHCO₃ and determined colorimetricaly (Olsen et al., 1954). Results were expressed in mg kg⁻¹ of soil. Base saturation was calculated as the ratio of the total exchangeable bases (Ca, Mg, K, and Na) to the CEC (obtained using NH₄OAc) and expressed as a percentage. The procedure is as follows;

Base saturation= (Total exchangeable bases)/CEC×100

Land degradation assessment

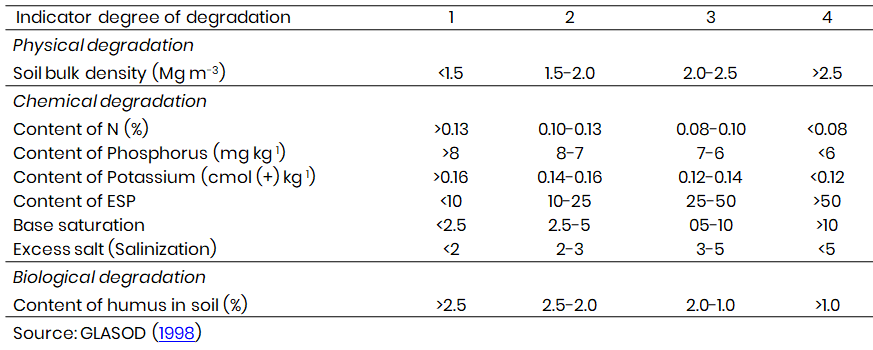

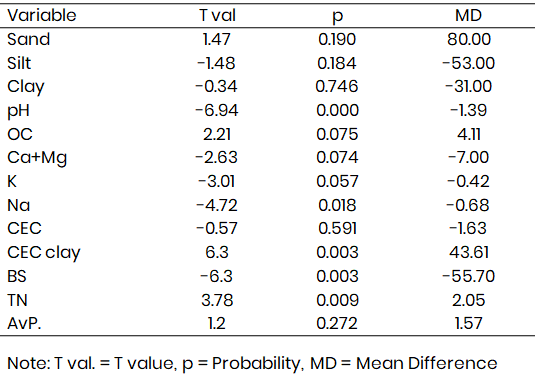

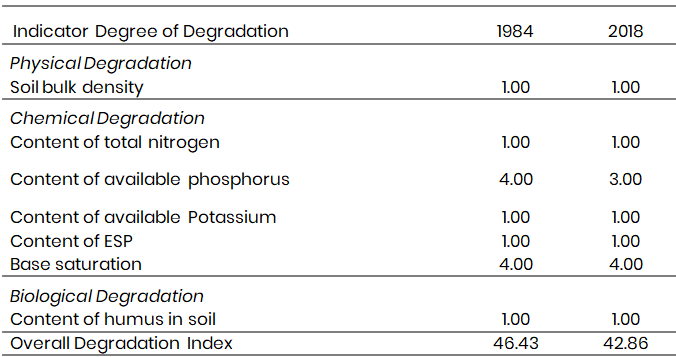

The level of soil degradation within the mango orchard, as well as data obtained from the legacy soil survey report of the site (Valette and Ibanga, 1984), was assessed using standard indicators and criteria for land degradation evaluation provided by the Global Assessment of Land Degradation (GLASOD, 1998), as outlined in Table 1. Table 2 provides an interpretation guide for evaluating the overall soil degradation level (FAO, 2004).

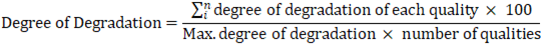

The degradation class was determined by matching the results of soil properties with the corresponding land degradation indicators. The degree of degradation was estimated mathematically using physical, chemical, and biological parameters, as shown in the equation below;

Table 1: Indicators and criteria for Land Degradation Assessment

Table 2: Key to interpreting overall degradation class

Statistical analysis

Impact of mango cultivation on soil properties was assessed using Student’s independent T-Test.

Results and Discussion

Impact of mango farming on soil properties

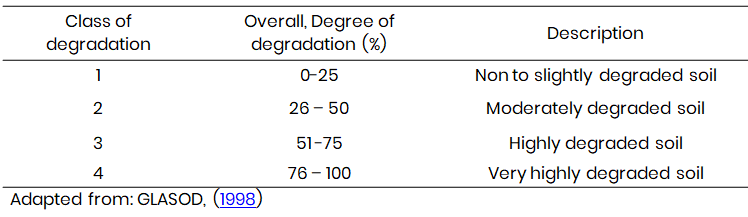

The results of the T-test reveal temporal changes in soil properties between the current study and the 1984 soil survey report (Table 3).

Soil Texture

There was increase in the sand fraction (T-value = 1.47, P-value = 0.190, mean difference (MD) = 80.00 g kg⁻¹). However, this increase was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). The observed increase in sand fraction could be attributed to the wide canopy of mango trees which reduces the impact of raindrops on the soil, minimizing erosion. The litter layer acts as a protective cover, reducing soil compaction and improving infiltration. Silt and clay fractions exhibited a non-significant decrease (T-value = -1.48 and -0.34, MD = -53.00 gkg⁻¹ and -31.00 gkg⁻¹, respectively). Negative T-values and mean differences indicate a decrease in these fractions, possibly due to the erosion of fine particles. This suggests that mango farming has minimal impact on the textural composition of the soil, which is largely determined by parent material and weathering processes.

Table 3: Impact of mango farming on some soil properties at IAR farm, Samaru

Soil pH

The significant decrease in soil pH (T = -6.94, p < 0.001, MD = -1.39) indicates decreased soil acidity under mango farming. This could result from organic matter decomposition, root exudates, or leaching of base cations. Sadia et al. (2023) and Aliyu et al. (2023) attributed higher pH in mango orchards to reduced leaching of basic cations, while Mosweu et al. (2013) suggested that canopy cover reduces evaporation rates, promoting conditions conducive to pH stabilization.

Organic Carbon

Soil organic carbon showed anincrease after 34 years of mango farming (T-value = 2.21, P-value = 0.075, MD = 4.11). This increase aligns with findings by Santos and Ribeiro (2002) in the São Francisco River Valley. Mango trees shed a significant amount of leaves, twigs, and flowers throughout the year. The decomposition of this organic material adds humus to the soil, which improves soil structure, nutrient availability, and water retention capacity.

Exchangeable Bases and CEC

The decline in Ca+Mg levels (T = -2.63, p = 0.074, MD = -7.00) is not significant, indicating possible nutrient leaching or uptake by mango trees. Mango plants require adequate supply of calcium and Magnesium for higher fruit production (Khan and Ahmed, 2020). The reduction in K (T = -3.01, p = 0.057, MD = -0.42) was significance, suggesting depletion due to high uptake or leaching, particularly in acidic soils. The significant decrease in Na (T = -4.72, p = 0.018, MD = -0.68) highlights potential effects of leaching or exchangeable sodium depletion. Aliyu (2023) attributed low exchangeable bases in soil to the absorption. Research shows that mango leaf litter contains appreciable amounts of magnesium, potassium and calcium, essential for plant growth (Kumar et al., 2021). There was a decline in CEC (T = -0.57, p = 0.591), although this decline was not significance suggesting stability in the soil's nutrient-holding capacity. The decline in CEC might be attributed with the decline in exchangeable bases above.

Total Nitrogen

A significant increase in TN (T = 3.78, p = 0.009, MD = 2.05) points to nitrogen enrichment, likely from organic inputs like leaf litter and application of nitrogenous fertiliser. The decomposition of mango leaves releases essential nutrients such as nitrogen replenishing soil fertility. The increase in nitrogen (N) concentration during the decomposition of mango litter and other organic materials has been noted by several researchers (Berg and McClaugherty, 2008; Prescott, 2005; Wei et al., 2023). This phenomenon often occurs as carbon (C) is lost more rapidly than nitrogen, leading to an increased N concentration in the remaining material. He et al. (2016) reported that nitrogen addition significantly increased soil dissolved organic N and inorganic N content.

Available Phosphorus

Available phosphorus increased (T-value = 1.20, p-value = 0.272, MD = 1.57 mg kg⁻¹) over the 35 years of mango cultivation. The increase in AvP is not significant, suggesting limited changes in phosphorus availability. Mango trees shed significant amounts of leaf litter, which decomposes and releases nutrients, including phosphorus, into the soil. Wei et al. (2023) reported that organic phosphorus in the litter is mineralized by soil microbes, making it available for plant uptake.

Impact of mango cultivation on soil degradation

Physical degradation

The degradation score for bulk density remained constant at 1.00 from 1984 to 2018, indicating no measurable physical degradation. This stability suggests that mango farming does not significantly compact the soil, likely due to reduced soil disturbance and organic matter contributions from the orchard.

Chemical degradation

Degradation score of total nitrogen stayed at 1.00 over the years, suggesting no degradation in total nitrogen levels. This aligns with the observed increase in TN in Table 3, likely due to organic inputs like leaf litter and nitrogen cycling under mango trees. The Degradation score of Available Phosphorus improved slightly from "very highly degraded" (4.00) in 1984 to "highly degraded” in 2018, reflecting reduced degradation. This could be due to better nutrient management, reduced erosion, or improved phosphorus availability from organic matter decomposition over time. A consistent score of 1.00 indicates no significant degradation of Exchangeable potassium levels, suggesting mango farming does not adversely affect potassium availability in this context. The score of Exchangeable Sodium Percentage (ESP) remained at 1.00, highlighting no degradation related to sodium accumulation. This aligns with Table 3, where sodium levels were reduced, suggesting effective leaching and absence of salinization. The Base Saturation of score remained at 4.00, indicating sustained chemical degradation related to base saturation levels. This is consistent with the significant decline in base saturation noted in Table 3, likely due to acidification and leaching of base cations.

Biological degradation

The content of humus in the soil is stable score of 1.00 suggests no biological degradation and implies that humus levels remain adequate under mango farming. This reflects the positive contribution of organic matter inputs from leaf litter and root biomass.

Overall degradation index

The overall degradation rate decreased slightly, from 46.43% in 1984 to 42.86% in the present study (Table 4), indicating slight improvement in soil properties over time. This is mainly attributed to improvements in the chemical properties like available phosphorus and stability in other indicators like humus content and nitrogen levels. This supports findings by da Silva et al. (2014) and Feng et al. (2020), which suggest that mango cultivation does not significantly deplete soil properties. The slight improvement in the overall degradation index suggests that mango farming, when managed properly, can sustain soil quality over time.

Table 4: Degradation scores for mango orchard at IAR farm, Samaru

Conclusion

The impact of mango cultivation on soil nutrient dynamics at the Institute for Agricultural Research (IAR) Farm in Samaru, Nigeria, reveals both beneficial and challenging aspects. Over the long-term, mango farming has contributed to the enhancement of soil organic carbon and total nitrogen levels, largely due to the significant input of organic material such as leaves and twigs. These organic materials decompose, enriching the soil with essential nutrients and improving soil structure, water retention, and microbial activity. However, there are notable declines in certain exchangeable bases, such as calcium, magnesium, and potassium, which may be attributed to both uptake by the trees and leaching. Although the cation exchange capacity (CEC) remained stable, phosphorus availability showed slight improvement over time due to microbial mineralization. Mango farming has also positively impacted the soil by reducing erosion and compaction through the canopy cover and organic litter. The degradation assessment showed that soil degradation in the mango orchard decreased slightly from 1984 (4.00) to 2018 (3.00), indicating that mango cultivation has not caused severe depletion of soil properties. The stability of key soil indicators, such as bulk density, base saturation, and humus content, further suggests that mango farming can be sustained with minimal impact on soil health when appropriate management practices are adopted. To improve the productivity of mango orchards while safeguarding soil resources and minimizing long-term degradation, the following recommendations are proposed to improve soil health and sustain mango cultivation at the Institute for Agricultural Research Farm, Samaru: Implement an integrated nutrient management strategies which combine organic and inorganic inputs to enhance nutrient availability while minimizing environmental impacts, mulching with mango leaves and other organic residues to enhance phosphorus recycling through litter decomposition should be encourage. Adopt soil conservation practices, such as cover cropping, mulching, and contour planting, to minimize water and wind erosion that contributes to sand loss. Lastly, encourage intercropping or agroforestry systems to diversify income sources and enhance soil fertility through complementary nutrient cycling.

References

Agbenin, J. O. (1995). Laboratory manual for soil/plant analyses. Department of Soil Science, Faculty of Agriculture, Ahmadu Bello University.

Aliyu, J., Shobayo, A. B., Ibrahim, U., & Abubakar, M. (2023). Fertility status of orchard soils at the Institute for Agricultural Research Horticultural Orchard. In F. A. Ajayi, S. A. Rahman, A. Usman, A. J. Ibrahim, S. O. Adejoh, H. A. Kana, S. A. Okunseboh, G. O. Ogah, D. B. Zaknayiba, & B. C. Okoye (Eds.), Strengthening agriculture for food and nutrition security, market development and export in a climate change environment: Proceedings of the 57th Annual Conference of Agricultural Society of Nigeria (pp. 544–547). Federal University Lafia.

Aliyu, J. (2023). Evaluation of the impact of continuous cultivation on soil development and quality at the Institute for Agricultural Research farm, Samaru, Nigeria (Doctoral dissertation). School of Postgraduate Studies.

Aminu, A. B., & Ladan, S. (2021). A review on the effect of soil amendments in plant nutrition and food security during COVID-19 pandemic in some parts of Nigeria. In Proceedings of the 39th Annual Conference of the Horticultural Society of Nigeria (pp. 1503–1514).

Balakrishna, M., Giridhara Krishna, T., Nagamadhuri, K. V., Sudhakar, P., Ravindra Reddy, R., & Yuvaraj, K. M. (2021). Soil fertility and leaf nutrient status of mango orchards in YSR district of Andhra Pradesh. The Pharma Innovation Journal, 10(10), 87–91.

Balarabe, M., Abdullah, K., & Nawawi, M. (2015). Long-term trend and seasonal variability of horizontal visibility in Nigerian troposphere. Atmosphere, 6(10), 1462–1486. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/atmos6101462

Berg, B., & McClaugherty, C. (2008). Plant litter: Decomposition, humus formation, carbon sequestration (2nd ed.). Springer-Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-74923-3

Blake, G. R., & Hartge, K. H. (1986). Soil bulk density and particle density determination. In A. Klute (Ed.), Methods of soil analysis (pp. 234–254). American Society of Agronomy.

da Silva, J. P. S., do Nascimento, C. W. A., Silva, D. J., da Cunha, K. P. V., & Biondi, C. M. (2014). Changes in soil fertility and mineral nutrition of mango orchards in São Francisco Valley, Brazil. Agrária – Revista Brasileira de Ciências Agrárias, 9(1), 42–48. https://doi.org/10.5039/ agraria.v9i1a3466

Copyright

Open Access: This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.