Mycological studies and pathogenicity of Tannia (Xanthosomas agittifolium) postharvest Tuber Rot

Abstract

Pathogenicity assays were conducted in 2021 and repeated in 2023 at the National Root Crops Research Institute (NRCRI), Umudike, Nigeria, to identify the primary aetiology of postharvest deterioration in decaying Xanthosomas agittifolium (tannia) tubers. Among the fungal isolates recovered, Penicillium spp. demonstrated the highest virulence, characterized by aggressive growth patterns and significant rot progression (27 mm). Rot initiation commenced upon mycelial contact of pathogens with tuber surface wounds, triggering a sequence of events. Upon contact, these fungi produced large quantities of oxalic acid and polygalacturonases, which acted synergistically. Oxalic acid sequestered calcium, lowering the pH to optimize endopolygalacturonase and cellulase activity. The advancing hyphae depleted pectic substances within tuber tissues, leading to peroxidase release via enzymatic activity. This sequential breakdown ultimately results in water-soaked, necrotic, and macerated tuber tissues.

Introduction

Cocoyams, comprising taro (Colocasia esculenta) and tannia (Xanthosomas agittifolium), are major tuber crops cultivated and consumed as staple foods across Africa, Latin America, the Pacific Islands, and Asia (FAO, 1993). Globally, cocoyams serve as a primary energy source for over 400 million people (Ubalua, 2016). Noted for their shade tolerance, Xanthosoma is particularly prevalent in southeastern Nigeria. While Colocasia is primarily used for soup thickening, Xanthosoma is boiled, roasted, or fried. A significant constraint to profitable Xanthosoma production is the short postharvest shelf-life of corms and cormels (2-5 months), limiting market potential and economic returns for farmers. Consequently, production lags behind major root and tuber crops like cassava and yam, exacerbated by disease susceptibility and limited planting material availability.

Flowering is rare in cocoyams, necessitating vegetative propagation and limiting genetic recombination. Despite their nutritional value, profitable production and storage of Xanthosoma remain hampered by microbial attacks. Xanthosoma corms and cormels are highly susceptible to microbial deterioration within 2-5 months postharvest. Reported storage losses in Nigeria are substantial. Postharvest physiological deterioration (PPD) discourages commercial production, storage, and utilization, restricting economic benefits for farmers and limiting supply to agro-industries. Optimal Xanthosoma storage occurs in cool, dry, well-ventilated environments for 2-5 months. At low temperatures (7°C), C. esculenta and X. sagittifolium can store for up to 4 months, while at higher ambient temperatures (25-30°C), storage may extend to 4-6 months (FAO, 2004). Conventional methods - such as barn heaping under shade, covering with straw/plantain leaves, wood ash application, pit storage with soil/leaf cover, or storage on wooden platforms with dry grass and occasional sprinkling - have proven ineffective beyond 5-6 months due to high losses. Leaving corms unharvested until needed is an alternative, yet all these methods fail to provide significant storage improvement. Recent suggestions for pre-storage fungicide dips (e.g., sodium hypochlorite within 24h postharvest) raises economic and health concerns, potentially limiting adoption by local farmers.

Cocoyam spoilage results from complex interactions between physical, physiological, and pathological factors. The disease was first reported in Ghana in 1945 (Posnette, 1945) and subsequently observed in various Nigerian states (Ishan Ekpoma, Etsako, Edo State in 1954; Bori, River State in 1955; Anambra, Imo, and Cross River in 1960), becoming epidemic in Nigeria by the late 1970s (Arene and Okwuowulu, 1997). Losses manifest as reduced quality and quantity. Storage deterioration typically initiates at wound sites incurred during harvesting and handling, providing entry points for pathogens. Initial infection by primary pathogens is often followed by secondary invasion by opportunistic pathogens and saprophytes colonizing necrotic tissues. Rotted corms/cormels exhibit blue/black or brown discoloration and foul odor within 2-5 months. Beyond microbial rots, physiological sprouting is another significant cause of storage loss, with reported losses of ~50% after 2 months and ~95% after 5 months (Paraquin and Miche, 1971). Conservative estimates indicate ~25% postharvest losses in the tropics (Coursey and Booth, 1972), though losses for C. esculenta in southeastern Nigeria can reach 76% during severe infections (Nwufo, 1980; Nwufo and Fajola, 1981).

Key pathogens implicated in on-farm and storage rots include Fusarium solani, Botryodiplodia theobromae, Rhizopus stolonifera, Aspergillus niger, Sclerotium rolfsii, Fusarium oxysporum, Pythium myriotylium, Penicillium spp., and Phytophthora infestans. Rot losses as high as 40-60% have been reported in Nigeria (Ubalua and Chukwu, 2008; Anele and Nwawuisi, 2008), underscoring the need for further research. Physiologically, cocoyam corms/cormels, like cassava and yam, are living structures experiencing endogenous respiratory and transpiratory water loss. These processes directly impact produce quality and susceptibility to microbial attack, leading to rapid tissue breakdown by pathogens within 2-5 months. Rot thus poses a major challenge to cocoyam cultivation, storage, and utilization due to inevitable harvest damage. Breeding programs, mutation breeding, and genetic engineering have yielded limited success in enhancing storability. This study aimed to isolate and identify fungal pathogens from rotten Xanthosoma corms and determine their relative roles and degrees of virulence in postharvest rot.

Material and Methods

Isolation, purification, and identification of pathogens

Fifty-three (53) decaying Xanthosomas agittifolium corms were sourced from the NRCRI, Umudike cocoyam barn. Corms were surface-sterilized with 70% ethanol and rinsed twice with sterile distilled water. Samples were dried on sterile paper towels in a laminar airflow hood for 10 minutes. Approximately 2 mm3 tissue sections were excised from the advancing margin of lesions (junction of healthy and decayed tissue) using a sterile scalpel. Sections were plated onto Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) and incubated at 27°C for four days. Plates were examined daily for fungal growth.

Purification and identification

Hyphal tips from the margins of developing mixed cultures were subcultured onto fresh PDA plates using flame-sterilized scalpels and incubated at 27°C until pure cultures were obtained. Pure cultures were identified microscopically and morphologically based on growth rate, colony color, mycelial morphology, and characteristics of sporulating structures and conidia, using standard taxonomic keys (Booth, 1971; Barnett and Hunter, 2000).

Estimation of pathogen frequency

The frequency of occurrence of isolated fungal pathogens was determined using thirty (30) additional decaying corms from the same source. Isolates were cultured separately on PDA. The presence of each isolate type in the 30 samples was recorded. Percentage occurrence was calculated as:

Percentage Occurrence = (Number of samples yielding a specific isolate / Total number of samples) × 100

Pathogenicity test

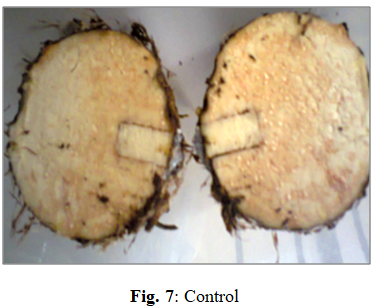

Healthy Xanthosomas agittifolium corms were washed with tap water and surface-sterilized with 70% ethanol. Corms were dried on sterile paper towels in a laminar airflow hood for 12 minutes. A sterile 5 mm diameter cork borer was used to create wells in the corms. Excised tissue plugs were retained in sterile Petri dishes. A 4 mm × 4 mm agar block from the actively growing margin of each pure test isolate was aseptically placed into a well. The well was sealed with sterile Vaseline to prevent contamination and labeled. Controls received sterile PDA plugs. The experiment was replicated five times per isolate. Inoculated corms were incubated in a polyethylene bucket at ambient conditions. After nine days, corms were cut transversely through the inoculation point. Rot diameter (mm) and lesion characteristics were recorded and compared to naturally diseased corms. Pathogens were re-isolated from lesion margins onto PDA. Pathogenicity was confirmed if the re-isolated pathogens exhibited identical microscopic, cultural, and morphological characteristics to the original inoculum.

Results and Discussion

Pathogen isolation and identification

Four fungal isolates were consistently recovered from the rotten Xanthosoma corms in both 2021 and 2023: Fusarium oxysporum, Penicillium spp., Botryodiplodia theobromae, and Aspergillus niger. Their morphological characteristics on PDA at 28°C were distinct:

- B. theobromae: Exhibited rapid growth, covering the plate in 48 hours. Mycelia were initially grey but turned black after 5 days, with spores transitioning from hyaline and aseptate to dark-brown.

- F. oxysporium: Colonies were whitish to pale pink, characterized by septate hyphae and elongated, curved macroconidia.

- Penicillium spp.: Colonial growth was moderate within 7 days. Conidiophores were dense and blue-green due to spore production, with flask-shaped phialides.

- A. niger: Displayed rapid growth, with a slightly brownish culture surface and a contrasting yellow reverse side. The conidiophores were upright and simple, terminating in a swelling bearing phialides.

Pathogen frequency and virulence

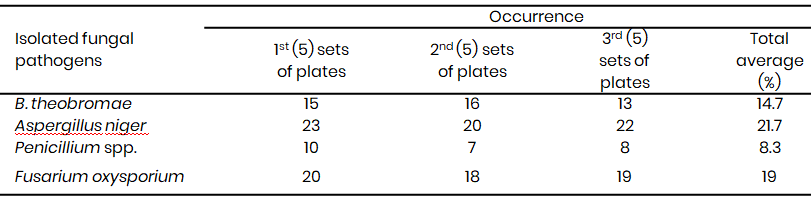

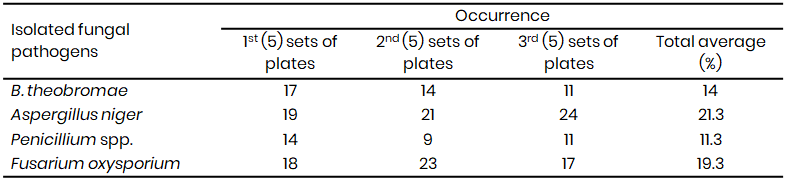

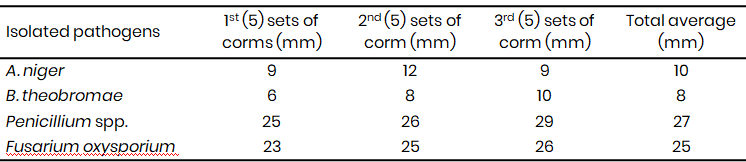

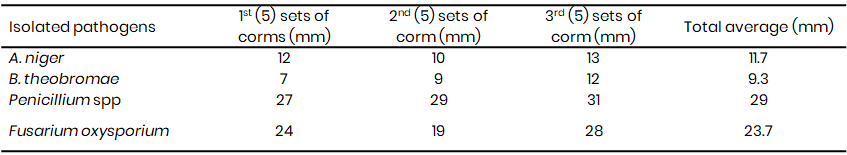

Penicillium spp. exhibited the lowest frequency of occurrence in the sampled rotten corms in both 2021 and 2023 (Table 1A & 1B). However, pathogenicity tests revealed that the Penicillium spp. were the most virulent pathogens, inducing the largest rot lesions (27 mm in 2021, 29 mm in 2023) (Table 2A & 2B), suggesting that the Penicillium spp. may be the primary causal agent of Xanthosoma postharvest tuber rot. In contrast, A. niger, while more frequently isolated (21.7% in 2021, 21.3% in 2023), caused significantly smaller lesions (10 mm in 2021, 11.7 mm in 2023) (Tables 1A & 1B, 2A & 2B). F. oxysporum also demonstrated high virulence (25 mm lesion diameter in 2021), while B. theobromae was the least virulent (8 mm lesion diameter) (Table 2A).

Disease development mechanism

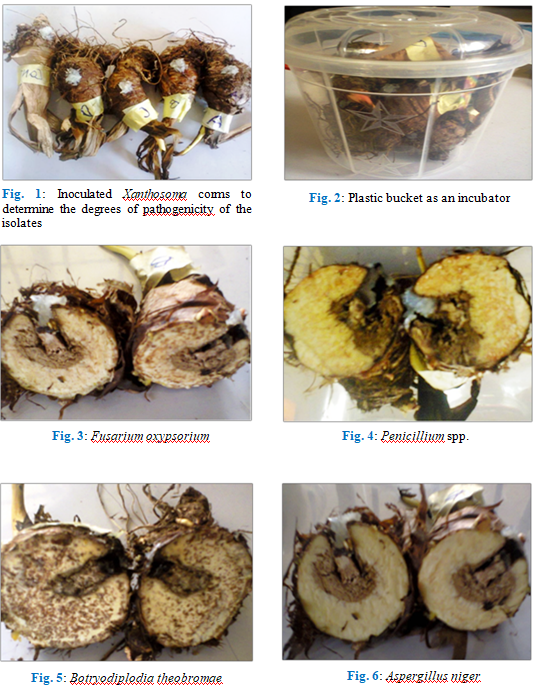

The ability of these isolates to induce rot on wholesome Xanthosomas agittifolium corms were investigated. Fig. 1 and 2 are typical representations of inoculation, incubation, and disease induction and progression in wholesome Xanthosoma corms after nine days of incubation.

Postharvest rot in cocoyams results from physical damage, physiological processes, and pathological factors, with pathogen attack being the most significant cause. Initial infection by primary pathogens (e.g., Penicillium spp.) facilitates subsequent colonization by secondary opportunists and saprophytes on necrotic tissues. The complex deterioration process involves enzymatic responses to wounding, originating from harvest/handling damage and spreading into storage parenchyma.

The growth rate varied from 3rd day to the 5th day while beyond the 6th day they attained their maximum growth rate covering the entire petri dishes. The mean radial diameter (Fig. 3-4) of the isolates differed significantly suggesting differences in the virulence of the isolates. While F. oxysporium and Penicillium spp. were more aggressive with an average diameter rot of 25 and 27 mm (Fig. 3 and 4) respectively, B. theobromae (Fig. 5) and Aspergillus niger (Fig. 6) recorded the least mean diameter of 8 mm and 10 mm respectively (Table 2A).

Table 1A: Percentage occurrence of the isolated fungal pathogens from the rotten Xanthosomas agittifolium corms (2021)<

Table 1B: Percentage occurrence of the isolated fungal pathogens from the rotten Xanthosomas agittifolium corms (2023)<

Table 2A: Induced infection on Xanthosomas agittifolium corms using the isolated fungal pathogens (2021)

Table 2B: Induced infection on Xanthosomas agittifolium corms using the isolated fungal pathogens (2023)

Pathogen penetration occurs intercellularly and intracellularly within the cortical parenchyma. Disease induction involves a sequence of events initiated by mycelial contact with the corm surface (Smith et al., 1984; Punja et al., 1985). The sequence of events leading to tissue maceration involves a synergistic biochemical attack:

- The fungi produce large quantities of oxalic acid and polygalacturonases upon contact with the corms.

- The oxalic acid serves to sequester calcium oxalate and lower the pH, creating the optimal acidic conditions for the maximum activity of key cell wall-degrading enzymes, endopolygalacturonases and cellulases.

- The advancing hyphae invade the tissue, depleting the pectic substances and stimulating the release of peroxidase via enzymatic activity.

- This degradation results in the characteristic water-soaked, necrotic, and macerated condition of the corm tissue.

Comparison with previous studies

The pathogens profile (B. theobromae, F. oxysporum, Penicillium spp. and A. niger) aligns with previous reports on Colocasia esculenta (taro) and cassava rots in southern Nigeria (Ugwuanyi and Obeta, 1996; Ugwuanyi and Obeta, 1999; Agu et al., 2014; Agu et al., 2016; Ubalua et al., 2020). While Ugwuanyi and Obeta (1996, 1999) also recovered Corticium rolfsii and Geotrichum candidum, differences in pathogen prevalence may be attributable to geographical location. The identification of these pathogens is crucial for understanding disease development patterns in Xanthosoma tubers.

Conclusion

This study identified Penicillium spp. as the primary causal agent of postharvest rot in Xanthosomas agittifolium tubers, despite its lower frequency of isolation compared to other fungi like A. niger. Its high virulence, demonstrated by the largest rot lesions (27-29 mm), underscores its significant role in postharvest deterioration. The disease mechanism involves synergistic production of oxalic acid and polygalacturonases by pathogens upon contact with wounded tuber surfaces, leading to pH reduction, optimal enzyme activity, pectin degradation, and ultimately tissue maceration.

Variations in pathogen prevalence and virulence observed between 2021 and 2023, and compared to other regions, highlight the influence of geographical and environmental factors. These findings provide a foundation for developing targeted management strategies against Penicillium spp. to mitigate postharvest losses in Xanthosoma.

References

Agu, K. C., Awah, N. S., Nnadozie, A. C., Okeke, B. C., Orji, M. U., Iloanusi, C. A., Anaukwu, C. G., Eneite, H. C., Ifediegwu, M. C., Umeoduagu, N. D., & Udoh, E. E. (2016). Isolation, identification and pathogenicity of fungi associated with cocoyam (Colocasia esculenta) spoilage. Food Science and Technology, 4(5), 103–106.

Agu, K. C., Awah, N. S., Sampson, P. G., Ikele, M. O., Mbachu, A. E., Ojiagu, K. D., Okeke, C. B., Okoro, N. C., & Okafor, O. I. (2014). Identification and pathogenicity of rot-causing fungal pathogens associated with Xanthosoma sagittifolium spoilage in South Eastern Nigeria. International Journal of Agriculture Innovations and Research, 2(6), 2319–1473.

Anele, I., & Nwawuisi, J. U. (2008). Comparison of the effects of three pathogenic fungi on cocoyam storage. In Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Conference of the Agricultural Society of Nigeria (pp. 183–186). Ebonyi State University, Abakaliki, Nigeria.

Arene, O. B., & Okwuowulu, P. A. (1997). The status of cocoyam research at NRCRI Umudike, Umuahia, Nigeria and the cropping package [Mimeograph].

Barnett, H. L., & Hunter, B. B. (2000). Illustrated genera of imperfect fungi (4th ed., pp. 1–197). CRC Press.

Booth, C. (1971). The genus Fusarium (p. 237). Commonwealth Mycological Institute.

Coursey, D. G., & Booth, R. V. (1972). The post-harvest phytopathology of perishable tropical produce. Review of Plant Pathology, 51, 751–765.

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). (1993). Production yearbook (Vol. 47).

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). (2004). Statistics Division: Major food and agriculture commodities and producers. Commodity by country. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. http://www.fao.org

Nwufo, M. I. (1980). Studies on the storage rot diseases of cocoyam (Colocasia esculenta) (Master’s dissertation, University of Ibadan).

Copyright

Open Access: This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.