Abstract

The present study analysed the various aspects related to casual labour households, focusing on income levels, market functioning, employment status, wage rates, and constraints faced by households in rural and urban areas of Udaipur district of Rajasthan, India. The study observed that the average income varies between rural and urban areas, with urban households earning more on average due to higher employment opportunities. Skilled labour earns higher wages and works longer hours, often receiving advance payments. Payment methods are predominantly time-based in rural areas and a mix of time-based and piece-rate in urban areas. Discrimination in wages, undercutting of wages, and lack of bargaining power are perceived issues, with many households feeling they have little freedom to reject offered wages. Wage rates vary across quarters and between male and female labourers, with urban areas generally offering higher wages due to more non-agricultural work opportunities. Constraints faced by casual labour households include low wage rates, lack of skills, poor functioning of government employment schemes, seasonal employment nature, prolonged work hours, and drudgery of work. These constraints are more pronounced in rural areas, leading to challenges in securing stable employment and adequate wages.

Introduction

The pattern of economic growth in any country has implications for the structural transformation of its labour force. Globally, majority of the total workforce (3.3 billion) is living in moderate or extremely poor conditions out of which about 61 per cent are employed in the informal sector (International Labour Organization, 2019). In informal/unorganized sector, workers are not able to organize themselves for their common goal due to various constraints like casual nature of employment, illiteracy, ignorance, and scattered and small size of establishments (Government of India, 1969). Casual labour is mainly unskilled or semi-skilled workers whose employment pattern includes a course of short-term jobs. Their investment and consumption pattern cognates into same category as they earn their livelihood by selling their man power and often regenerate it by ‘investing’ a significant part of their wage-earnings on food items (Mishra and Lyngskor, 2007). They work either in their own or nearby villages or to nearby cities for employment opportunities.

In India, nearly 95 per cent of the informal/ casual labour does not have any written job contracts, and the chances are also significantly low in getting a daily employment in the market (PLFS, 2018-19). At national level, about 56 per cent and 41 per cent of the below poverty line cards were owned by casual labour working in the agriculture sector and in non-agriculture sector, respectively (National Sample Survey, 68th round, 2011). This distribution shows that casual labour households are living in a low dietary consumption levels in India. Due to the low consumption, casual workers are often poor performers and their efficiency is also very low. The market forces often times impose on them the vicious cycle of inefficiency - low wage rates - low consumption - inefficiency. That’s why majority of the casual labour is living in severe food-insecure conditions (Chakravarty and Dand, 2006). The average monthly income of farm households (for which casual labour is the primary occupation) is ₹ 8,931 (NABARD Report, 2016), which is not enough to satisfy their basic livelihood needs and a quality life. This poor sector spends a higher share of their expenditure on food and other essential requirements and oftentimes obtains their food from subsistence production, market, and transfers from government programs or from other relative households (Baiphethi and Jacobs, 2009). This low level of food consumption is a sincere livelihood problem as it increases risk of physical, social and mental issues (Nord, 1999).

In Indian context, urban casual labour is divided mainly into two types: (i) skilled labour or karigar, which includes skilled labour in the field of marble or tile fixing, wall plastering, wall preparation, wall painting, etc. and (ii) unskilled workers engaged in activities such as loading and unloading of trucks, preparation of building materials, etc. In case of rural casual labour, skilled labour is related to work such as agriculture, construction and painting of houses and unskilled workers are engaged in agricultural work, MGNREGA (public work programme), and other village work activities. This urban and rural divide of casual labour in emerging countries like India is characterized by comparatively higher income in urban areas on account of higher employment opportunities and wage rates.

Further, despite the fact that scholars have begun to push for the study of casual labour market, there has been little policy implementation at the international level and even less at the local level. Therefore, the current research is an exclusive attempt to study the casual labour cross the rural and urban divide based on primary data concerning various important economic parameters. The implications of the study will be useful in specific programme and policy recommendations that address the insecurity of casual labour and can act as a link to the debate of rural bias particularly among the informal or unorganised sector of casual labour.

Materials and Methods

Data

The study is based on primary data collected at two intervals i.e. August-September, 2019 and January-February, 2020 from the Udaipur district of Rajasthan (largest state of India). Udaipur district was purposively selected as it has the highest number of agricultural labour i.e. 3,02,968 (6.13 % of total agricultural labour in Rajasthan) and is fifth largest in terms of total worker population (13,65,783) in the state (Government of India, 2011). The district is a home to various indigenous communities including Bhil, Meena, Damor and Gharasia since approximately 50 percent of the tribal population of Rajasthan is located in this district (District Census Handbook, 2011). Poverty and malnutrition are especially prevalent amongst these indigenous communities and their occupation is dominated by agriculture with small landholding, undulated land and irrigated area. These communities have a higher incidence of illiteracy, poverty and malnourishment, and they face geographic and social isolation. The district lacks irrigation facilities, productive land, skill-building and other employment opportunities in the villages. Therefore, a large number of tribal and other rural people migrate to the city to earn their livelihood with makes it suitable to investigate the rural and urban divide in terms of consumption pattern and food security.

Sampling Design

The casual labour was divided into two categories viz., category I[1] and category II[2] casual labour households. A comprehensive list of all casual labour market points was prepared in the Udaipur city of Rajasthan and four points i.e. Hathipole Circle, Pratapnagar Circle, MallaTalai and Reti Stand were selected based on the maximum number of casual labour availability. Thereafter, 40 labourers were selected through a judgmental or purposive sampling method from each point, respectively and were considered under the category I of casual labour. In order to make a valid comparison, an equal number of casual labours in category II based on similar economic conditions were purposively selected from villages or nearby places. Therefore, a total sample size of 320 casual labour households was considered for the present study collected at two intervals from 2019-2020.

[1]Category I: Urban casual labour households who were engaged in different farm or non-farm activities in Udaipur city for at least 100 days in a year.

[2]Category II: Rural casual labour households who were engaged in different farm or non-farm activities within or nearby the village for at least 100 days in a year.

Analytical tools and methods

Data collected were tabulated and analyzed to fulfil the specific objectives of the study. The tools, which were used for the analysis of the data, are presented and discussed below. After the collection of raw data, with the help of the schedules, these were compiled and tabulated as required for analysis.

Status of the casual labour market

The different features of the labour market such as money wage rate, kind wage, number of days worked, frequency of wage payment, working hours, and employment pattern in Udaipur district of Rajasthan were computed by applying simple statistical tools such as frequency, percentage and sample mean.

Constraints faced by casual labour

To identify and prioritize the constraints faced by casual labour in the study area, households were asked to rank. These ranks were analyzed through Garrett’s ranking technique. Garrett’s ranking technique gives the change of orders of constraints into numerical scores. The significant advantage of this technique as compared to simple frequency distribution is that in this technique constraints are arranged based on their importance from households.

The Garrett’s formula for converting ranks into per cent was given by the following expression:

|

Percent position =

|

(Rij – 0.5)

------------------------

Nj

|

× 100

|

Where,

Rij = rank given for ith constraints by jth individual and

Nj = number of constraints ranked by the jth individual.

The relative position of each rank obtained from the above formula was converted into scores by referring to the critical values given in Table by Garrett and Woodworth (1969) (transmutation of orders of merit into units of amount or scores) for each factor; scores of all individuals were added and then divided by the total number of households for the specific factor (constraint).

Results and Discussion

Income level of casual labour households

The main source of income to the sample casual labour households was the wages of human labour. The income level of casual labour in both categories is depicted in Table 1. The total average income earned by the sample casual labour households was ₹ 10265, which varied from ₹ 8100 in rural areas to ₹ 11931 in urban areas, respectively. Across the class intervals, most of the respondents (35.93%) earned income between ₹ 6001 to 9000 per month followed by between ₹ 3001 to 6000 (22.81%), between ₹ 9001 to 12000 (20.65%), between more than ₹ 15000 (9.06%), between ₹ 12001 to ₹ 5000 (8.43%) and less than ₹ 3000 (3.12%). The number of people earning less than ₹ 3000 per month varied from 5 percent in rural category to 1.25 percent in urban category. In urban category, the majority of casual labour households earned monthly income between ₹ 6001 and ₹ 9000, whereas it was reported to be lower in the case of rural category (₹ 3001 to ₹ 6000). Only 2.50 percent of the sample rural casual labour households were earning a monthly average income of more than ₹ 15000, whereas it was higher in the urban category (15.62%). The urban category was receiving 33.59 percent more than the monthly national average income of ₹ 8,931 (NABARD Report, 2016). Whereas the rural casual labour households were reportedly receiving 9.30 percent lower than the national average. It was because of higher employment opportunities in the urban areas with direct implications on the sample households' income levels and food security.

Table 1: Income-wise distribution of sample casual labour households

Status and functioning of casual labour market

The key features of the functioning of the casual labour market in the study area are shown in Table 2. The table showed that the urban casual labour market was divided mainly into two types: I skilled labour or karigar, which includes skilled labour in the field of marble or tile fixing, wall plastering, wall preparation, wall painting, etc.; and (ii) unskilled or helpful workers engaged in activities such as loading and unloading of trucks, preparation of building materials, etc. In urban casual labour households, the number of days worked per month for both types of work was found to be 25 days per month. The daily wage rate in the casual labour market in urban casual labour households was found to be ₹ 385 for unskilled labour, and ₹ 690 for skilled casual labour. Reddy and Kumar (2006) also reported higher wage rates for skilled labour on the market. Women in the urban casual labour market are mainly engaged in unskilled types of activities, such as construction and housework. Similar findings were also reported by Dave (2012).

In the urban casual labour market, working hours in the peak season were 9.55 hours per day for unskilled labour, and 10.02 for skilled labour, and in the slack season the corresponding figures were 8 hours per day for unskilled labour, and 8.56 hours per day for skilled labour. Skilled labour normally employed for a longer period, so that their hours of work were found to be greater than unskilled labour in urban casual labour households. Asiwal et al. (2018) also reported that in the casual labour market, the average number of hours worked by labour exceeded 8 hours (standard norms).

There was much less provision of advance wages in the urban casual labour market. Employers were found not to be giving advance wages in the case of unskilled labour, because unskilled labour usually works for a very shorter period, and there was also a chance or fear of them not coming to work after receiving advance wages. The skilled urban casual labour households mainly work for a longer period in the construction sector or any other activity, so sometimes employers or contractors find that they provide advance wages for casual labour, which is only 7 percent. Two factors could be attributed to the advance payment of wages for skilled casual labour. The first factor was that both employers and workers belonged to the same villages and did not suffer from moral hazards. Second, the payment of a certain amount of wages in advance ensures that the employer secures the supply of labour at the required time and saves the cost of the transaction.

The basis for payment in the urban casual market is divided into time and piece rate. Payment of wages for casual labour households based on a piece rate, mainly or for works such as unloading of trucks, was also made for construction work based on a time rate. It was found that 80.05 percent of the payment of wages made in terms of time and 19.95 percent of the payment of wages was made based on the rate of pay for unskilled casual labour. The corresponding figures were 91.67 percent and 8.33 percent for skilled urban casual labour. The wages for urban casual labour were revised back in the study area two years ago.

The table also showed that, in the rural casual labour market, labour was also divided into two types, i.e. skilled labour, which includes skilled labour related to agricultural work, construction and painting of houses, etc., and unskilled workers engaged in agricultural work, MNREGA, and other village work activities. Most of the labourers have worked in their own villages as well as in nearby villages for most of the time. The average number of casual working days per month, ranging from 17 days in the case of skilled casual labour, to 15 days in the case of unskilled casual labour in rural casual labour market. The daily wage rate in rural casual labour was found to be equal to ₹ 275 for unskilled labour, and ₹ 575 for skilled casual labour. In some cases, it has also been observed that there is a small amount of money borrowed by casual labourers who have repaid their wages by deduction. Women in the rural casual labour market are mainly engaged in agriculture, construction, and household-related work. A majority of casual labour has been found to work in public works in rural areas.

Average working hours for rural casual labour, during peak season, exceed 8 hours of standard labour, which were 9.75 hours per day for unskilled labour, 9.89 hours for skilled labour, and in the slack season, approximately 7 hours per day for unskilled labour, and 7.45 hours per day for skilled labour. Employers or contractors found that they were providing advance wages to casual labour, which was 5 percent in the case of skilled rural casual labour, and 3 percent in the case of unskilled rural casual labour. The majority of casual labours did not receive any snacks/meals from the employer, yet some of them received special snacks/meals in the case of agricultural labour.

On average, 92.75 percent of unskilled rural casual labour received wages on a time-based basis and 8.25 percent on a piece-based basis, compared with 87.65 percent and 12.35 percent for skilled rural casual labour, respectively, on the rural market. The wages of rural casual labour households, such as urban casual labour households, have not been revised in the study area for the last two years.

The results of the study clearly showed that there were more opportunities for urban casual labour, compared to rural casual labour. Wage rates were also found to be higher for both skilled and unskilled casual labour in the urban labour market. Casual work hours were also higher in urban casual labour in both peak and slack seasons. In the urban casual labour market, the piece rate was found to be higher compared to rural casual labour, and the rate of time was found to be more prominent in rural casual labour, compared to urban casual labour. The last wage revision in both categories of casual labour was carried out in the study area two years ago. It can also be concluded that prevailing wage rate in the study area was found to be higher than the minimum wage fixed by the government of Rajasthan in both skilled and unskilled casual labours. Employment opportunities in urban areas were found to be far better than rural areas and that the wage rate was also higher, leading to a higher level of income for casual work in urban casual labour.

Table 2: Functioning of casual labour market

Salient features of the functioning of casual labour market

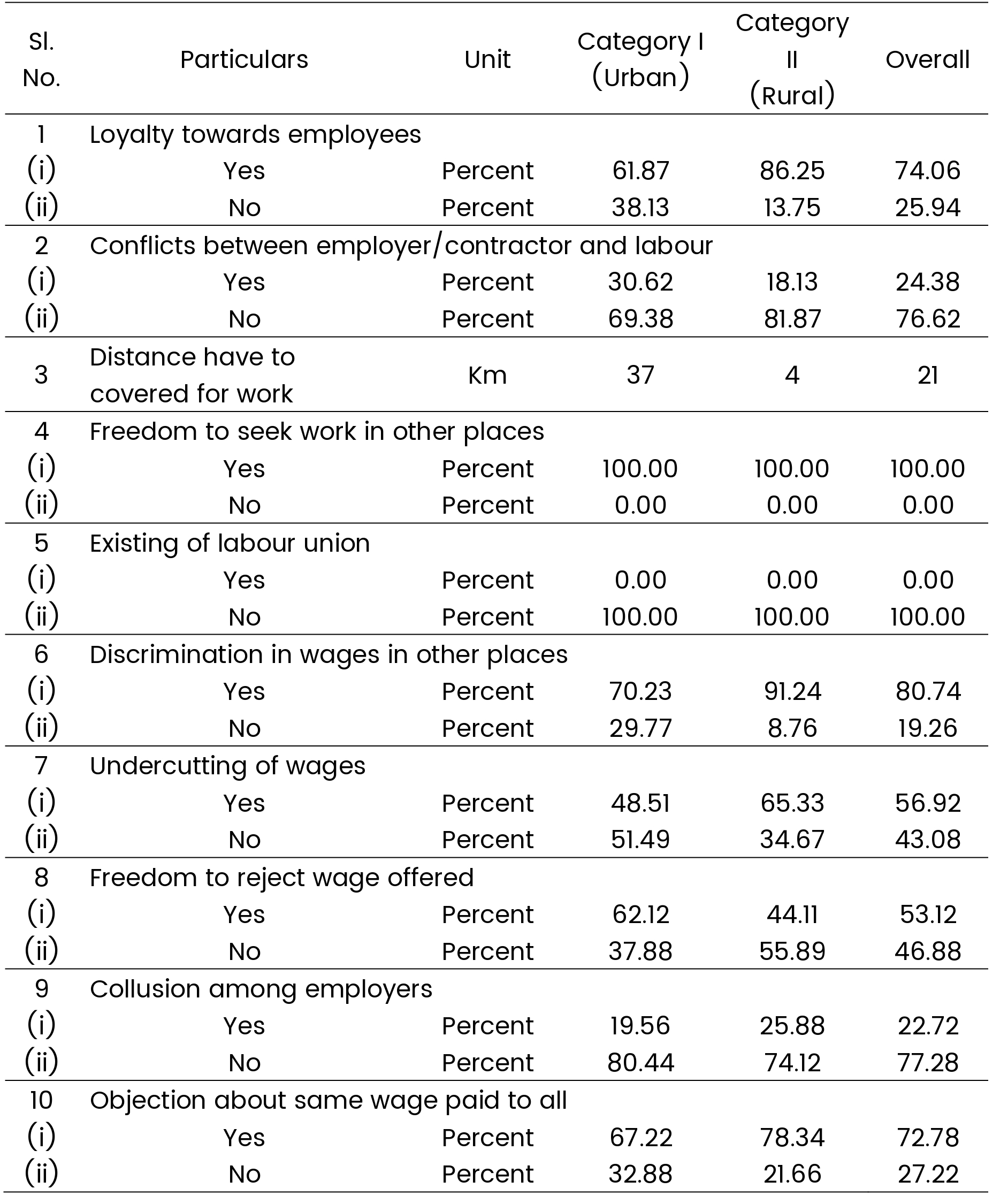

The opinion of the sample of casual labour households on some other important aspects of the functioning of the labour market is summarized in Table 3. In the case of casual labour in the study area first, 74.06 percent of labour households believed in loyalty to their employers. Second, 76.62 percent of labour households reported no conflict with their employers, and 24.38 percent reported that they had a conflict mainly over non-payment of wages on time. Third, the sample of labour households reported that they covered 21 km. Fourth, they were free to work elsewhere, and fifth, there was no labour union in labour households. Sixth, 80.74 percent of casual labour households believed that there was discrimination in wages in other places. Seventh, 56.92 percent of the sample of casual labour households faced undercutting wages and the remaining 43.08 percent did not face cuts in wages. Eighth, 53.12 percent of casual labour reported having the freedom to reject the wage offered, and 46.88 had no freedom to reject the wage offered. Ninth, 77.28 percent reported that there was no collusion between employers, and the remaining 22.72 percent reported that there was collusion between employers. Tenth, 72.78 percent of urban casual labour objected to the same wage paid to all, and the remaining 27.22 percent did not have any objection about the same wage paid to all.

First, 61.87 percent of urban casual labour households believed in loyalty to their employers. Second, 69.38 percent of labour households did not report any conflict with their employers; there were some cases of conflict mainly over non-payment of wages on time. Third, all the sample labour reported that they had travelled 37 km to work. Fourth, they were free to work elsewhere, and fifth, there was no labour union in casual labour. Sixthly, 70.23 percent of urban casual labour households believed that there was discrimination in wages in other places. Seventh, 51.49 percent of the sample urban casual labour households did not face undercutting wages and the remaining 48.51 percent faced lower wages. Eighth, 62.12 percent of urban casual labour households reported that they had the freedom to reject the wage offered and 37.88 percent were not free to reject the wage offered. Ninth, 80.44 percent reported that there was no collusion between employers, and the remaining 19.66 percent reported that there was collusion between employers. Tenth, 67.22 percent of urban casual labour households objected to the same wage paid to all, and the remaining 32.88 percent had no objection to the same wage paid to all.

First, in rural casual labour households, 86.25 percent of workers believed in loyalty to their employers. Second, 81.87 percent of labour households reported no conflict with their employers, and 18.13 percent reported some cases of conflict with their employers. Third, all the rural casual labour households reported going 4 km to work every day. Fourth, one-hundred percent of rural casual labour households were free to work elsewhere, and fifth, there was no labour union. Sixthly, 91.24 percent of rural labour households believed that there was discrimination in wages elsewhere. Seventh, 65.33 percent of the sample of rural labour households faced undercutting wages and the remaining 34.67 percent did not face cuts in wages. Eighth, 55.89 percent of urban casual labour households reported that they had no freedom to reject the wage offered, and 44.11 were free to reject the wage offered because of the less availability of work in rural areas. Ninth, 74.12 percent reported that there was no collusion between employers, and the remaining 25.88 percent reported that there was collusion between employers. Tenth, 78.34 percent of rural labour households objected to the same wage paid to all, and the remaining 21.66 percent had no objection to the same wage paid to all.

It can be summed up that the majority of casual labour households, who believed in loyalty to their employers, did not report any conflict with their employers, covered 21 km, were free to work elsewhere, did not have a labour union, believed in discrimination in wages elsewhere, faced undercutting wages, reported freedom to reject the wage offered, reported no collusion and had objection to the same wage paid to all.

Table 3: Salient features of the functioning of casual labour market

Employment status of casual labour

The employment and unemployment status of casual labour is shown in Table 4, which shows that, in the urban category of casual labour households, average working days were 25 days per month with 4 days of unemployment and urban casual labour was not available on one day in a month due to various issues such as family or individual health, social reasons, etc. The probability of employment was 0.86 in the case of urban casual labour. This indicates that the chances of working for rural casual labour were 86 times and that they could not get work 14 times.

Average working days for rural casual labour households were found to be 16.00 days per month with 12.50 days of unemployment and 1.50 days of non-working days per month due to various issues such as family or individual health, social reasons, etc. The probability of employment for rural casual labour was 0.55. This indicates that the chances of working for rural casual labour households were 55 times higher.

Average working days in urban casual labour households were 25 days higher than rural casual labour households (16 days). The probability of employment was also found to be higher in the case of urban casual labour households (0.86) compared to rural casual labour households (0.55).

It can be summed up that urban casual labour households had better job opportunities than rural casual labour households, that’s why a lot of casual labour travelled daily from their villages to Udaipur to earn wages.

Table 4: Employment status

Average daily wages of casual labour

Wages are, by and large, the only source of income for casual labour in the study area. As such, the only determinant of casual labour earnings is the rate of pay and the extent to which work is available in a month or year (Chitodkar, 1992). Table 5 and Table 6 show the average daily wage earnings of all the casual labour sampled during the study period. It is important to note that the average urban casual labour wage was found to be the highest in the quarter I (April-June), which was ₹ 323 for male labour and ₹ 291 for female labour with an average wage of ₹ 304 due to the summer season, and mainly construction activities were carried out at the prime level during that period. The lowest average wage earnings (₹ 287) were recorded during quarter II (July-Sep) consisting of a maximum of ₹ 296 per day for male labour and a maximum of ₹ 278 per day for female labour due to less availability of work during the rainy season. The average wage earnings for quarter III (Oct-Dec) and quarter IV (Jan-March) were ₹ 317, and ₹315 for male and ₹ 280, and ₹ 282 for female labour with an average wage of ₹ 298 and ₹ 299, respectively. Asthana and Medrano (2001) also reported the difference in wages for male and female labour.

Table 6 shows that, in rural casual labour, average daily wage earnings in non-public works ranged between ₹ 252 (quarter I) and ₹ 297 (quarter IV) for males, and similarly, ranged from ₹ 192 (quarter I) to ₹ 203 (quarter IV) for females during different periods. The highest wage earnings were recorded in quarter IV (approximately ₹ 250) and quarter III (approximately ₹ 243) due to higher employment in agricultural activities such as harvesting in winter and rainy season. Swamikannan and Jeyalakshmi (2015) also reported maximum employment in agriculture during the rainy and winter seasons. The MGNREGA Act enhances the security of households' livelihoods in rural areas of the country and provides for at least 100 days of employment in every household in the financial year for which adult members volunteer to do unskilled manual work. Table 6 shows average wage earnings in public works ranging from ₹ 134 (quarter II) to ₹ 165 (quarter IV) for males and ₹ 100 (quarter II) to ₹ 130 (quarter IV) for females. In public works such as MGNREGA, the lowest wage earnings (₹ 117) were recorded during the quarter II period due to the rainy season in the study area.

The results suggest that these casual labour working partly in agriculture and in partly in non-agricultural activities in rural areas and casual labour working only in non-agricultural activities in urban areas. The average wage rate for urban casual labour, therefore, was higher than that for rural casual labour. All those labours who go for work outside the village are earning a much higher daily wage than those who worked in the village. It can be concluded that wage earnings ranged from one quarter to the next quarter, as well as between male and female labour. The differential wage rate is one of the important factors for labour migration in the study area.

Table 5: Average daily wage earnings of urban casual labour

Table 6: Average daily wage earnings of rural casual labour

Constraints faced by casual labour

In order to analyze the constraints faced by casual labour households, major problems identified during the visits were presented to the sample of casual labour households and asked to rank them according to the severity of the constraints and analyzed using the Garrett ranking technique. All the constraints faced by casual labour households discussed in the following sub-headings:

3.7 Constraints related to employment opportunities

Table 7 depicted the constraints related to employment opportunities and perceived that low wage rates and unavailability of work as a major problem with a Garrett score of 78.27, lack of skills (63.78), poor functioning of MGNREGA (63.47), seasonal nature of employment (51.33), prolonged work hours (48.57), drudgery of work (44.55), low bargaining power (39.04), no labour union (32.48) and misbehave with labour by employment provider (27.08) were the major constraints related to employment opportunities securing second, third, fourth fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth and ninth rank, respectively. There are a very large number of casual workers working in urban and rural areas, so there were not enough job opportunities for all casual workers, which also reduced their bargaining power. Dave (2012) also reported constraints such as lack of skills, long working hours, poor working conditions, occupational hazards, low wages for labour.

Urban casual labour perceived that low wage rates and unavailability of work ranked first with a Garrett score of 77.32, lack of skills (69.21), poor functioning of MGNREGA (56.21), seasonal nature of employment (53.20), prolonged work hours (50), drudgery of work (45.40), low bargaining power (39.32), no labour union (32.30) and misbehave with labour by employment provider (27.04) were the major constraints related to employment opportunities securing second, third, fourth fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth and ninth rank, respectively.

Rural casual labour households perceived that low wage rates and unavailability of work ranked first with a Garrett score of 79.22, poor functioning of MGNREGA (70.74), lack of skills (58.34), seasonal nature of employment (52.32), prolonged work hours (47.14), the drudgery of work (43.70), low bargaining power (38.76), no labour union (32.66) and misbehave with labour by employment provider (27.12) were the major constraints related to employment opportunities securing second, third, fourth fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth and ninth rank, respectively.

It can be concluded that the main constraint faced by households was low wage rates and unavailability of work and, at the very least, misbehaviour of labour by the employment provider.

It can be summed up that casual labour households in the study area believed that large family size, lack of capital, lack of availability of hospitals/health centres and health services, lack of availability of schools/Anganwadi centres/colleges, lack of public contact of labour with information sources, lack of pucca houses, low wage rates and unavailability of work were the major constraints faced by the casual labour households.

Table 7: Constraints related to employment of casual labour

Suggestions and Recommendations

The study noted that there is no single platform for casual labour, where they can unite to discuss various issues related to them. There is often a conflict between casual labour and employers on a variety of issues, such as undercutting wages, working hours, and many other disputes. The Government should, therefore, set up a common platform to address various issues related to casual labour. The study shows that a low wage rate; a lower number of working days and low family earnings prevail in rural areas. Existing rural activities must be renovated in light of the minimum needs of casual labour. Rural development opportunities need to be created through the establishment of agro-based industries, particularly in rural areas, so that rural labour can work at a decent wage rate for a reasonable number of days.

Acknowledgements

This research article is derived from the PhD Thesis of Dr Vikalp Sharma under the guidance of his Major advisor Dr G.L. Meena linked to the MPUAT Udaipur.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest in this study.

References

Asiwal R C, Kumawat D K and Sharma R C. 2018. Study of Micro-Evidences for Agricultural Labour Market Functioning in Agriculturally Developed Chomu Tehsil of Jaipur. Current Agriculture Research Journal 6(3): 436-440.

Asthana M D and Medrano P. 2001. Towards Hunger Free India: Agenda and Imperatives: Proceedings of National Consultation on 'Towards Hunger Free India', New Delhi, pp. 24-26

Baiphethi M N and Jacobs P T. 2009. The Contribution of Subsistence Farming to Food Security in South Africa. Agrekon 48(4): 459-482. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03031853.2009.9523836

Census of India. 2011. Series 09 - Part XII B - District Census Handbook, Jaipur, pp. 1-1150

Chakravarty S and Dand S A. 2006. Food Insecurity in Gujarat: A Study of Two Rural Populations. Economic and Political Weekly 41: 2248-2258.

Chitodkar A B. 1992. Wage determination and labor market dynamics in rural India: A study of Maharashtra. Journal of Development Economics 38(1): 167-186.

Dave V. 2012. Women Workers in Unorganized Sector. Women’s Link 18(3): 9-17.

Garett H E and Woodworth R S. 1969. Statistics in Psychology and Education. Vakils, Feffer and Simons Pvt. Ltd., Bombay. pp. 329.

Government of India, 2018-19. Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, National Statistical Office, Report on Periodic labour force survey (PLFS).

Mishra S K and Lyngskor J W. 2007. Munich Personal RePEc Archive, Paper No. 1810.

National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development. 2016-17. Report on All India Rural Financial Inclusion Survey (NAFIS).

Nord M, Jemison K and Bickel G. 1999. Prevalence of Food Insecurity and Hunger, By States 1996-1998, Food Assistance and nutrition Research Report No. 2, Food and Rural Economics Division, Economic Research Services, United States Department of Agriculture.

Reddy B M and Kumar S. 2006. Rural labour markets and agricultural wage rate determination: A case study of Andhra Pradesh, India. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 49(4): 851-870.

Swamikannan D and Jeyalakshmi C. 2015. Women Labour in Agriculture in India: Some Facets. International Journal of Business and Economic Research 1(1): 22-28.

Copyright

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.